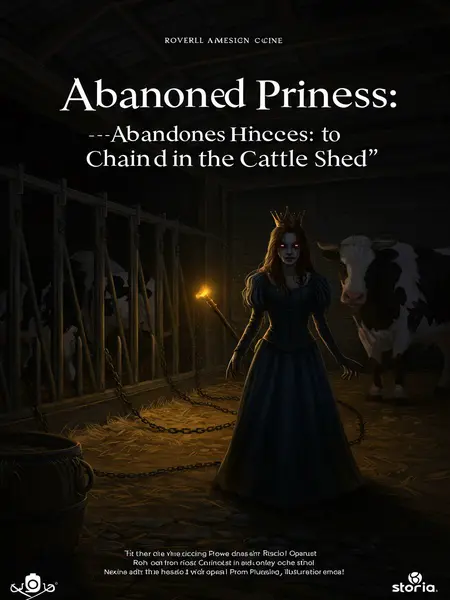

Chapter 1: Exile from the Cattle Shed

My mother was the Rajkumari of Kaveripur. Even now, the old palace in Kaveripur smells of sandalwood and dust—every stone remembers her footsteps.

She was the pride of our land once, her laughter ringing through the palace courtyards, her feet adorned with silver payals. The maids would hush their gossip when her anklets chimed down the marble steps. Everyone in Kaveripur would bow their heads as she passed, murmuring, 'Jai Rajkumari.' The memory of those days lived on in the stories Dadi would whisper at dusk, the lamp’s wick dancing in the monsoon breeze.

During the chaos of war, the invading tribes captured her and dragged her far to the grasslands, locking her away in a makeshift cattle shed.

That night, as the city burned and conch shells wailed in terror, I clutched the end of her dupatta, stumbling as we were herded along, my tiny feet bleeding from thorns. The grasslands stretched endlessly—miles and miles of shivering green, the wind howling like a vengeful chudail. In that wretched cattle shed, they tossed us in with the cows, treating us like stray animals.

Every day, different men trampled on her dignity.

They would come in groups, the reek of bidi smoke and country liquor thick in the air. Sometimes I would bury my face in the old jute sack Ma gave me, trying to block out her sobs and their cruel, jeering laughter. My fists clenched, nails digging crescent moons into my palms, wishing I could grow up in a second—strong enough to fight them all off.

She was tormented until her mind broke, calling out each day, "Pitaji Maharaj, save me..." But only more brutal humiliation answered her prayers.

Some days, she curled up on the muddy floor, rocking herself, whispering names I didn’t know—her old dolls, her childhood friends, her father the Raja, the city that had forgotten us. Sometimes she’d whisper names and snatches of lullabies—"Nindiya re, tu aa ja re"—the words tangled with her tears. The only answer was the slap of wet cow dung on the walls, the mocking shouts outside. I used to wonder if the gods could hear prayers from a cattle shed.

Until I turned eight, when she used all her strength to throw me out of the cattle shed.

"Get out!"

It was a dark, windy night. In a daze, someone lifted me and hurled me out, hard.

I remember the whistling wind that night, like a banshee’s cry. The stars were hidden, the moon behind a smoky veil. Someone’s hands—bony and cold—gripped my arms tight. Half-asleep, I flew through the air for a moment, then slammed into the packed earth outside.

"Aah..." I woke up from the pain. The earth was cold against my cheek, damp with last night’s rain. I propped myself up with my thin limbs and saw my usually dazed mother standing coldly at the edge of the cattle shed, her face pale as a ghost.

The faint lantern inside flickered just enough to outline her. Her hair, once shining and braided with jasmine, now hung matted over her face. She swayed, bare feet caked in mud. The ache I felt wasn’t just from the fall, but from seeing her like this—her eyes unseeing, face as lifeless as the moon.

I was born able to see at night, but she had long since been blinded.

I never understood why darkness never bothered me. Even on pitch-black nights, I could make out every stone and weed. Ma, though, would stumble and reach out blindly, her eyes dull and white. It was as if the world had shut her out, leaving her only the memory of light.

I instinctively stepped towards her.

"Ma..."

The word was barely a whisper, trembling with hope and fear. My heart thudded, louder than the distant jackal howls.

"Get out!" Her hands gripped the bamboo fence tight. "Go as far away as you can. Mat aana wapas, samjhi? Teri shakal dekh ke aur bhi gussa aata hai."

Her voice was harsh, like she’d swallowed sand—nothing soft left in it. But I saw her knuckles turn white around the bamboo. Her shoulders heaved with every breath. For a moment, I wondered if she was crying, but the wind dried any tears before they could fall.

After saying this, she groped her way back into the herd, the iron chain around her ankle clanking loudly.

The sound of the chain echoed in the stillness—like temple bells at midnight, but twisted and cruel. She didn’t look back, just shuffled among the cattle, her form fading into the darkness and the soft lowing of the cows.

I stood outside the cattle shed, not daring to climb back in. I was afraid she would hate me even more.

My toes curled in the cold mud. I rubbed my arms to chase away the goosebumps, wishing for the old red shawl Ma used to wrap around me during winter. The fear of her anger was sharper than any hunger. I’d rather shiver outside than face that look of disgust again.

I had no father, nothing at all—I only had my mother.

Sometimes I tried to imagine what a father’s hug would feel like—warm, safe, the way other children in stories had. But all I had was Ma, and even that seemed to slip away.

I squatted in a corner outside the cattle shed, quietly inching closer.

The wall of the cattle shed was rough against my back, but I found a spot hidden by the shadow of a big buffalo. Even being this close made my heart lighter, as if the distance between us was lessened by a few feet.

"Get out!" Ma seemed to sense I hadn’t left and shouted at me.

Her voice was sharper this time. A nearby cow startled, shifting its weight, and a bell clanged inside.

"Why don’t you just die? Even hearing your breathing disgusts me!"

Her words were like slaps. I bit my lip so hard it almost bled, trying not to let her hear even a single sob. My chest felt tight, as if my lungs were packed with river mud.

Frightened, I hugged myself tightly.

I dug my fingers into my thin arms, rocking slightly, hoping the world would swallow me for a while. The wind nipped at my toes. My breath came out in white puffs, mixing with the fog. Somewhere, a cow’s tail swished, and the smell of dung mixed with the faint sweetness of stale hay.

Most of the time, Ma wasn’t like this. In her dazed and broken state, she would secretly hide me under a cow to drink milk and give me the clean roti to eat first.

Sometimes, when the world was quiet, she would stroke my hair gently, calling me her "chhotu," and sneak me a bit of jaggery saved from the invaders’ rations. In those moments, I almost forgot the war, the men, and the chain. There was only Ma, humming old lullabies from her childhood, the same ones her own mother must have sung.

But every month, there were always a few days when she would suddenly become fierce and terrifying, just like tonight.

Dadi used to say, “Sometimes even the moon turns dark, beta. But it always comes back.” I hoped Ma’s anger was like that—passing, not forever.

But never as fierce as tonight.

There was a wildness in her eyes, even though they were blind. Her voice echoed outside, bouncing off the silent grassland. Even the cows shuffled nervously, as if they too sensed something different.

She probably sensed I was still not moving, and actually threw cow dung at me.

A wet, heavy thud hit my foot. I jumped back, startled, wiping the filth off my leg. It was the first time she’d ever done that. Shame burned my face hotter than any slap.

"Get out!"

Her words were a curse, spat with venom. The sound lingered in the air, refusing to fade.

"Fine, if you won’t leave, then I’ll die... so I won’t feel you anymore..."

The suddenness of her words sent a chill down my spine. My mouth went dry, my mind racing to understand if she really meant it.

Saying that, she actually tried to run herself into the stone block.

In that moment, I saw her groping blindly, her fingers brushing the cold stone, her body tensed as if to fling herself headlong. My heart nearly stopped.

I hurriedly stood up. "I’ll go... I’ll go right away..."

My voice cracked. The fear in my chest burst out, and I stumbled to my feet, not even caring about the cold anymore. I raised my hands, palms out, to show her I was leaving. "Dekho, Ma, main jaa rahi hoon... please, don’t do anything."

Ma can’t die. If she dies, then I really have nothing left.

I remembered the story of Sita Maa walking into the earth, and a wave of terror washed over me—what if my Ma vanished too? No one would even know, or care.

The people on the grassland say, as long as you trap the cow, the calf can’t escape.

I’d overheard the herdsmen say this many times, usually while tying up a stubborn calf. I was always the calf, never the cow—weak, helpless, always tethered to Ma’s side, even if she didn’t want me.

I am that calf.

I had originally wanted to stay in the corner and wait until Ma became the other Ma again before going back to keep her company.

I would wait, sometimes for hours, until the madness passed and she would let me crawl back into her lap, stroking my hair, whispering half-forgotten palace stories. But tonight was different—the look in her eyes made me think she might really never let me return.

But she wouldn’t let me stay near the cattle shed.

No matter how quietly I tried to breathe, she would sense my presence, as if she had some sixth sense. I could hear her whispering to herself, talking to shadows and gods, her voice rising whenever I crept close.

No matter where I hid, she could always locate me by sound, staring at me with those blind eyes on her pale face.

Even when I held my breath, my heartbeat seemed too loud. Her head would turn, unerringly facing me, the milky eyes boring through the darkness. Sometimes I wondered if she was cursed to always sense my misery.

As long as I didn’t leave, she would go and bang herself against the stone block.

The scrape of her chain on the stone haunted me, every sound stabbing at my heart. I pressed my hands to my ears, wishing the world would go silent for once.

In the end, I left.

I looked back one last time. Ma was just a shadow by the cattle shed, barely more real than the ghosts in Dadi’s stories. The wind howled, urging me to move on.

I thought I’d go a bit farther first and come back in a couple of days to see her.

Just two days, I promised myself. Maybe she would be better then. Maybe she would forgive me for being born. I clung to that hope, even as I shivered in the cold.

To see if she had changed back.

The grassland is vast, and the winter wind is especially cold. Besides the cattle shed, I didn’t know where else could be my home.

I wandered, the icy wind cutting through my thin kurta. My nose ran, my toes went numb. Every shadow seemed a threat. The only world I knew was that cattle shed and Ma’s arms, even if they pushed me away now.

Passing by a mud hut, I felt the warmth coming from inside, so I quietly sat down, leaning against it.

The hut was small, its thatch roof patched with tarpaulin and old gunny sacks. The faint glow of a lantern peeked out from between the woven sticks. I pressed my back to the warm mud, closing my eyes, letting the heat seep into my frozen bones.

Inside, I heard the voices of herdsmen talking.

Their words drifted out with the smell of fried onions and mutton. My stomach growled, but I held still, hoping they wouldn’t notice me.

A woman asked coldly, "Hajiya, when can we finish off that mother and daughter in the cattle shed? Keeping them is a waste of food."

Her voice was sharp, almost bored, like someone discussing which chicken to slaughter. I felt a shiver run down my spine. The contempt in her tone was as cold as the wind outside.

Then a man sighed.

A deep, tired sound, as if he’d carried a lifetime of burdens on his shoulders. I could imagine his weathered face, lines etched deep by sun and sorrow.

"Arif, not yet. The older one is a princess after all, and now war has broken out again. Maybe she can still be useful."

There was a pause, the sound of a glass being set down, maybe tea sloshing over the rim. I heard someone scratching their beard thoughtfully.

"What use? Didn’t Kaveripur say they’ve already found the Rajkumari? Clearly they’ve given up on the real one..."

There was bitterness in her tone, as if she’d seen too many broken promises and dead ends.

"The real one is always the real one, Hajiya. This year’s weather is too bad, the cows can’t breed, and food is indeed scarce in winter. If you think they’re wasting rations, why not kill the little one first."

His words were so casual, it chilled me. As if killing a child was no different from butchering a goat. I bit my tongue, tasting blood, and tried to press myself further into the mud wall.

"That works."

Her words settled in the air like a death sentence. I barely dared to breathe, my heart hammering wildly in my chest. My fingers dug grooves into the earth, wishing I could simply melt away.

Their words sent a chill down my spine.

For a moment, my mind went blank. I didn’t even notice the tears that started to leak from my eyes. The world outside seemed to tilt—suddenly, nowhere was safe.

By accident, I knocked over the iron spade by the hut.

It clattered loudly, a harsh metallic sound slicing through the night. I froze, mouth open, blood roaring in my ears.

"Thud!"

The sound echoed, followed by the barking of a dog somewhere nearby. I cursed myself silently—such a stupid mistake.

"Who’s outside?"

The woman’s voice was shrill now, like a crow caught in a storm. I heard feet moving quickly across the earthen floor.

My heart tightened, and I ran.

I didn’t think, just pushed off the ground and sprinted blindly into the darkness, feet flying over stones and grass, breath coming in harsh bursts. I could feel them behind me, shouting, grabbing at bows and arrows.

The two of them quickly lifted the curtain and came out.

The fabric rustled, and the door banged against the frame. I dared not look back, only ran faster.

"It’s too dark, can’t see clearly..."

The man’s voice was gruff, annoyed. There was a clatter—someone fumbling with something heavy.

"Get my bow."

A "whoosh" sound.

The wind changed, carrying the sharp hiss of an arrow slicing the night. My eyes widened, and I tried to duck.

My hair stood on end. I dodged instinctively, but still, the arrow struck my back.

A burning pain seared through my shoulder. I stumbled, tripping over my own feet, the world spinning wildly.

Pain surged, my vision went black, and I fell forward.

I hit the ground hard, the air knocked out of my lungs. For a moment, all I could hear was the blood rushing in my ears and the distant, triumphant cries of the herdsmen.

At that moment, a giant white dog leapt out from the tall grass, grabbed me by the back, and ran off at full speed.

Its fur was thick, warm, and it smelled faintly of smoke and wild flowers. I barely registered what was happening—one moment, pain; the next, the ground moving beneath me as I was dragged away, bumping and jostling through the tall grass.

Bumping along, I tried hard to look back in my Ma’s direction. In a blur, I seemed to see her leaning on the fence, anxiously watching me.

Through my tears and dizziness, I caught a glimpse of her silhouette—frail, bent over the bamboo fence, her head tilted as if straining to hear. For a second, I imagined she was searching for me, that she cared.

I pulled a bitter smile at the corner of my mouth.

A crooked, painful grin twisted my lips. Even at the end, hope clung to me like a stubborn burr. I wanted to believe she loved me, even when I knew better.

"Still dreaming that Ma cares for you even as you die, fool. You’re such a filthy thing, how could she love you? Death is better, at least you won’t disgust her anymore."

That voice in my head sounded too much like the herdswoman, too much like my own secret fears. I choked down a sob, feeling the coldness seep through my veins.

"Ma, farewell forever. I wish you an early return home, reunion with your family, happiness and peace year after year..."

The wish was a whisper, carried away by the wind. I imagined her once more in the palace garden, laughter tinkling as she ran to embrace her father, her brother by her side. If only wishes were horses...

After that, darkness swallowed me. Somewhere, far away, a conch shell sounded again—was it for me this time?