Chapter 4: Crossing the Line

Everyone got angry when they heard this.

They swarmed up. Knuckles whitened around lunch trays, jaws clenched, a few guys shifting their weight like they were ready for anything. You could feel the temperature in the room spike by ten degrees.

They grabbed Mike by the collar and were about to hit him. My heart hammered. One wrong move and we’d be on the six o’clock news for all the wrong reasons. If this went south, we’d be blacklisted from every lunch spot from Parma to Lakewood.

“You’re talking nonsense! Who’s starving for your food? If Foreman Derek wasn’t decent, saying your whole family relies on this deli, who would eat your lousy food?” one of the guys shouted, voice cracking with outrage.

“So now that business is good, you’re burning the bridge after crossing it. You two are just ingrates!” Another worker spat on the floor, arms crossed tight.

When I first met Mike near my daughter’s school, he was wearing old jeans and looked miserable. His sneakers were threadbare, and he kept glancing at his phone, worried and waiting.

I chatted with him and learned both his parents were bedridden, his oldest son was in high school, and his younger daughter was in middle school. It wasn’t easy for him, and that tugged at my heart—a familiar American story of scraping by and hoping for better.

I felt bad for him, so I bought twenty lunches from him for the crew to try. It was my way of paying it forward, and maybe giving him a shot at steady business.

At that time, everyone brought their own food.

It was a hassle, and in summer it spoiled fast, in winter it froze. I remember biting into a half-frozen sandwich in February, longing for anything hot.

When they heard lunch was $4.50 and filling, everyone was happy. For the price of a fancy coffee, you got a meal that stuck to your ribs.

So Mike started making lunches for the job site. Every day at noon, his beat-up Camry would pull up, trunk full of steaming Styrofoam boxes.

I didn’t expect that after just three years, he was already tired of it. It’s like we’d gone from lifeline to burden, just because business was good.

Seeing the guys were about to get physical, I hurried to stop them. I raised my hands, stepped between Mike and the crew. “Enough! Nobody’s getting arrested over a dinner roll, not today,” I said, my voice firm but calm.

These guys have endless strength from working construction all year. If they lost control and someone got hurt, it would be a disaster. I pictured HR paperwork, police cars, and the whole site shut down over deli drama.

I found a few guys who were relatively calm and persuaded the others to leave first. I kept my tone low, reminding them we were better than this.

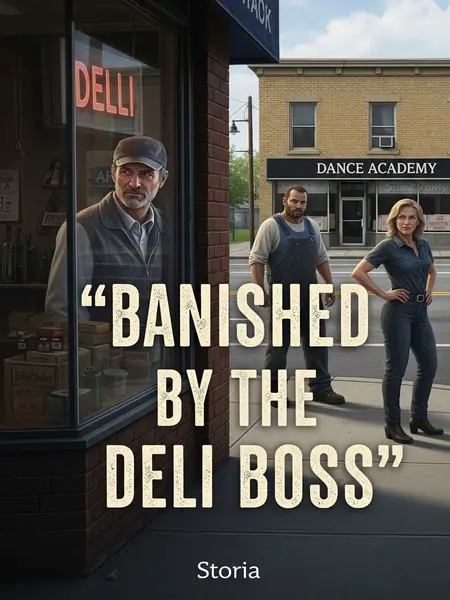

Then I calmly asked Mike,

“Mike, I buy groceries and cook at home too, so I can estimate. Even if our guys eat a lot, you’re clearing at least a buck a box, and that’s with us eating like linebackers. You’ll miss that money when it’s gone.”

“We have more than two hundred guys eating here. If you don’t do our business, you’ll lose almost $2,000 a month.” I let the numbers hang in the air, hoping reason would win out.

Mike was dismissive.

“Derek, I won’t hide it from you. The reason I keep lowering your standards is because I don’t want your business anymore.” He said it like he was finally getting something off his chest.

He nodded at the dance academy, where a line of girls in pink hoodies and messy buns were stretching on the steps, oblivious to the drama.

“See that? That school has over a thousand students. They want to keep their figures, so they eat very little and want less oil, less salt, less seasoning.”

“In a month, I save a ton just on seasonings.” He grinned, as if penny-pinching was a badge of honor.

“Same $4.50 lunch, the students’ cost isn’t even a quarter of yours. Your business? I’d rather not do it. Anyway, we never signed a contract.”

Mike was right. Choosing to eat lunches is a personal choice, and because we trusted him, we never signed a contract. But trust, once broken, doesn’t mend easily.

But…

I looked across the street and almost laughed. The irony was thick as winter fog.

That dance academy is run by my wife. The school built a cafeteria, but it wasn’t finished yet, so the students had to figure out lunch for now.

Some students bring their own food, and the rest make do with Mike’s lunches. They eat in small groups on the front lawn, picking at lettuce and sipping on water bottles with names in Sharpie.

But yesterday my wife told me, the cafeteria will be ready to open in a week. Then Mike would be out the biggest slice of his business, and he didn’t even see it coming.

Thinking of this, I sighed. “Alright, Mike. Since you don’t want our business, we’ll find somewhere else to eat from now on.” I squared my shoulders, signaling to the crew it was time to leave.

Mike’s wife hurried over to pull me back. Her face was tight with worry, her voice low. “Derek, please, don’t walk out. We’re grateful for every lunch you guys buy. Mike’s just... stubborn sometimes.”

She was still reluctant to lose our "small change."

But Mike shouted at her.

“Don’t let this guy fool you! We’re the only deli for miles around. The other places charge $6 just for a bowl of plain noodles—do you think they can afford that? They’ll still have to bring their own food.” He puffed out his chest, like he’d already won.

“When they get tired of bringing food and come begging to me, lunch won’t be $4.50 anymore, it’ll be at least $6.” He smirked, certain we’d be crawling back.

Looking at him so smug, I felt sick and decided to leave with the rest of the guys. Pride is a bitter taste, but sometimes you have to walk away.

But Mike grabbed me.

“Don’t go! After your scene just now, the crew left, but I made all these lunches for you, you have to buy them all.” He blocked the door with his bulk, not budging.