Chapter 2: The Taboo Returns

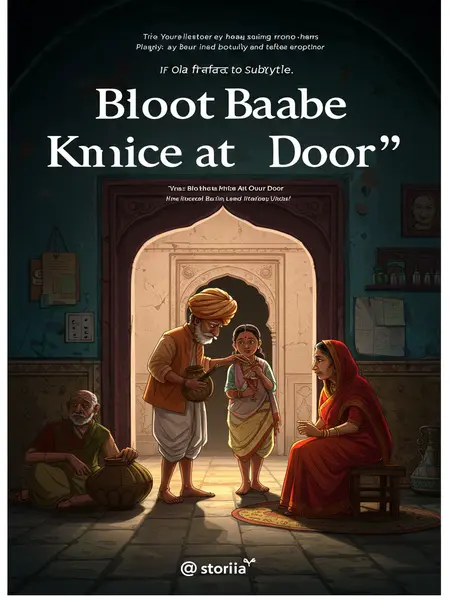

I asked in confusion, “What’s Bhoot Baba?”

I’d heard the name whispered among cousins before, but never from the grown-ups. My heart thudded, unsure whether to laugh or shiver.

Panting, my uncle replied, “The one your dadi always talks about—the Bhoot Baba that eats naughty children. That’s what we just saw.”

He wiped his brow, voice hushed and urgent. Even the stray dogs near the lane seemed to sense something odd, backing away from the gate.

I stammered, “No way? I thought it looked just like a person.”

The words came out small and uncertain, my mind scrambling to find a logical explanation. After all, monsters only existed in stories, right?

“Bas, don’t say anything.” My uncle’s voice was thick with fear, and he ran even faster.

His grip on my arm tightened. “Log sun lenge toh poora mohalla pareshan ho jayega,” he muttered, as if afraid even the air might overhear.

As soon as we entered the courtyard of our old colony house, he slammed the gate shut and bolted it.

The clang of the bolt echoed in the quiet afternoon. Our old colony house, with its mossy walls and squeaky swing, suddenly felt like a fortress.

My dadaji came out to greet us.

He was wearing his checked lungi and an old sweater. The smell of his tobacco pipe hung in the air. “Arrey, Munna, what happened?”

“Munna, why are you sweating so much? Go warm up by the heater, don’t—”

Before dadaji could finish, my uncle interrupted, “Baba, I saw Bhoot Baba.”

My uncle’s words stopped everyone in their tracks. Even the TV playing in the neighbour’s house seemed to grow quiet.

Dadaji’s dusky face instantly darkened.

He put down his pipe, his eyes narrowing. The lines on his face seemed deeper suddenly, like he’d heard the worst news.

“You went into the old jungle?”

His voice was heavy with disbelief and anger. In our family, the old jungle was only spoken of in hushed tones.

My uncle replied guiltily, “Hmm.”

He looked down, rubbing his feet on the mat, as if wishing he could disappear.

Dadaji’s slap echoed; even the neighbour’s radio seemed to pause. My uncle stared at the floor, rubbing his cheek, not daring to meet Dadaji’s eyes.

“No one’s set foot in that jungle for over twenty years, and you just had to go risk your life.”

The shame in his words was worse than the slap. “Log kya kahenge agar kuch ho jata?” he muttered under his breath.

Even the paanwala at the corner would lower his voice when mentioning the jungle after sunset. The old jungle is an unspoken forbidden zone in our town.

It’s the kind of place that kids dare each other to run past after dusk, but no one ever does. The bushes always seem to rustle with secrets, and elders won’t let the kids even play cricket near its edge.

The last person who accidentally entered never came out.

Whispers went around the bazaar for months. People would cross themselves unconsciously when walking nearby, and no one dared look too long at the jungle’s edge after sunset.

The whole mohalla heard his heart-wrenching screams for half an hour, but no one dared go in to check.

That night, every house kept their doors double-bolted. Mothers clutched their children close, and prayers lasted longer than usual. Even the pandit performed a hawan at the temple the next day.

My uncle and I had committed a grave taboo.

It was the kind of thing people would mutter about for years, glancing at us with half-fear, half-pity. The family’s name could’ve been ruined if something had happened.

Holding his swollen cheek, my uncle tried to explain, “We were chasing a rabbit. The fog came up and we couldn’t see, so we went in by mistake.”

He looked like a schoolboy caught bunking class, voice faltering. His eyes darted to the floor, avoiding dadaji’s glare.

Dadaji took a deep breath and asked, “How do you know it was Bhoot Baba?”

His tone was softer now, but every word was loaded with tension.

“He stretched out his arm and waved at Sonu. That arm was nearly seven feet long.”

The words hung in the air, making my skin crawl. My uncle’s hand shook as he described it, his other hand pressed to his cheek where the slap still burned.

I thought for a moment. “Maybe the waving arm hit a tree branch, so it just looked that long.”

I tried to sound brave, but my voice was barely a whisper. I wished I believed my own words.

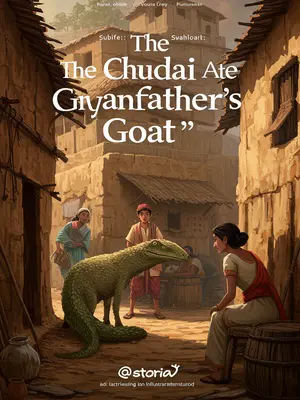

My uncle said, “That fur, it was black, with a yellow ring around the neck. Isn’t that exactly how the demon Bhoot Baba looks?”

He looked around, as if expecting someone to contradict him, but no one did. A chill seemed to settle in the room.

I said, “That yellow thing, I thought it looked like a muffler.”

Trying to recall, I remembered my own woolen scarf, yellow with red checks. Maybe it was just someone’s muffler. Still, doubt gnawed at me.

Dadaji said, “Munna, did you see clearly or not? Bhoot Baba coming out of the jungle is a deadly matter. Diwali is coming soon—don’t make a mistake, or no one will have a peaceful festival.”

He ran a hand through his thinning hair, glancing at the calendar on the wall with ‘Shubh Deepawali’ written on it. “Hamare ghar ka sukh shanti tumhare haathon mein hai,” he said gravely.

My uncle thought for a while, then became less certain. “I think it probably was.”

He looked helpless, eyes darting between dadi and dadaji, almost wishing for reassurance.

Dadaji paced back and forth for a long time, head down.

The floor creaked under his weight. The entire house seemed to be holding its breath, even the old ceiling fan had stopped squeaking.

Finally, with a grave expression, he said, “You two shut all the doors. I’m going to find the panchayat head. No matter who comes, don’t open the door.”

His words left no room for doubt. In our town, the panchayat head was the highest authority, almost like a judge, and if he got involved, the matter was serious.

Dadi went into the house and grabbed several skyrocket firecrackers, stuffing them into dadaji’s pocket.

She handed them over with trembling hands, muttering a quick prayer, “Hanumanji raksha karna.” She even tied a little red thread around his wrist for protection.

Dadaji, pipe in mouth, left the house.

His back looked smaller as he walked out into the fog, but his stride was steady. The gate clanged shut behind him.