Chapter 3: Nursery Fears

The atmosphere inside turned tense immediately.

The TV’s sound faded into the background. My heart thudded as I watched the shadows flicker on the walls. The faint scent of incense from the morning puja still lingered, but it did nothing to calm me.

A cold sweat broke out all over me from fear.

I kept rubbing my palms on my pants, trying to hide my trembling. Even my breath came out in little shivers.

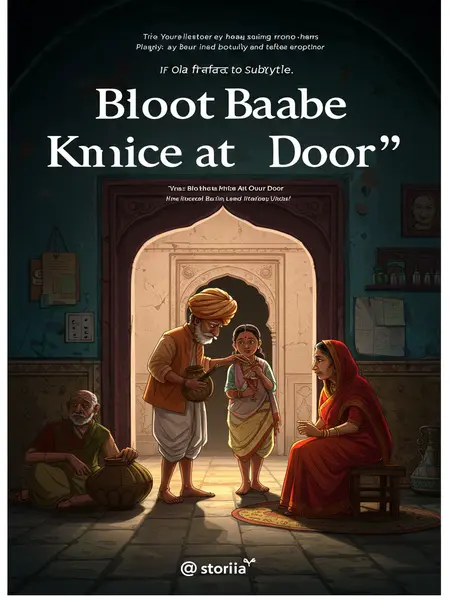

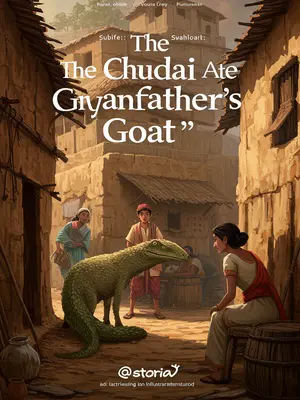

Bhoot Baba is every child’s nightmare here.

We’d scare each other with stories on the terrace at night, pretending to be brave, but secretly everyone was afraid to go to the bathroom alone after dark.

There’s a nursery rhyme that’s been passed down for generations:

“Red eyes, green nose, four hairy hooves. Walks with a dhap-dhap sound, wants to eat live children.”

Every time someone sang it, the younger kids would cover their ears and hide behind their mothers’ sarees. The older ones would just laugh nervously. Even the bravest kid would shut up, glancing at the dark corners of the room.

This is about Bhoot Baba.

Even the mention of his name would make the wind seem to howl louder. No one would dare whistle after sundown, lest Bhoot Baba mistake it as a call.

Legend says Bhoot Baba is over seven feet tall, with green eyes as big as lanterns. It can stride over thirty feet at a time and especially likes to come out at night to catch and eat children.

The aunties would talk in hushed voices at the water pump, warning the younger ones not to stay out late during festivals or new moon nights.

It eats people from the inside out.

The way the elders described it, you could almost feel your own stomach twisting.

First, it removes the organs. After eating them, the person still looks like a complete skin sack.

Then it pulls out the bones, one by one, and chews them up.

After chewing, it props up the skin sack with straw, making it look like a living person.

It then stands this straw man at your door.

You could imagine it, a lifeless figure standing like a scarecrow, eyes blank, head drooping, as if waiting for something.

It keeps watch beside it.

When a family member opens the door, whoever comes out gets eaten.

It keeps eating until the whole family is gone.

Only then does it eat the skin.

After finishing the skin, it goes to the next house.

No wonder the lanes would fall eerily silent after sunset, every house drawing its curtains and bolting the doors tight.

If a child cries at night, as long as an adult says, “Stop crying, Bhoot Baba will hear and come catch you,” the child doesn’t dare make another sound.

Even the bravest kid would stop mid-whimper, clutching a pillow, eyes darting to the shadows under the bed.

Originally, after I started primary school, I didn’t believe Bhoot Baba really existed. I thought it was just something adults said to scare kids.

It was a way to keep us in line, or so I thought. But the fear in the air tonight felt too real, too raw.

But seeing my dadaji and uncle’s expressions, it seemed like it might be real.

Dadaji, the pillar of strength in our family, had never looked so unsettled. My uncle’s hands still shook as he poured himself a glass of water.

I asked my dadi, “Does Bhoot Baba really exist? Have you ever seen it?”

Dadi fiddled with her sari pallu, eyes darting to the window as if expecting something to loom out of the darkness.

Dadi swallowed and said, “It really exists. Over by the old jungle, more than twenty years ago, there was one living there. Whenever a family had a newborn, it would come out at night to do harm. Back then, a family had twins, a boy and a girl. Bhoot Baba ate them both, not even a trace was left. Ever since then, whenever a family was about to have a child, they’d hide elsewhere. With no newborns, it started eating older kids. Later, it didn’t matter—adult or child—if it caught you, it ate you. When it stood up, it was taller than a house. Its eyes were bigger than our steel thalis, and green. Several strong young men who weren’t afraid tried to kill it together, but in the end, not even their skin sacks were left. Finally, the whole mohalla joined forces and blasted it with a desi cannon. The corpse lay there, and it took eight strong men to carry it away. Then they dug a pit, threw it in, poured kerosene, burned it, and buried the ashes. It’s been over twenty years since anyone’s seen it. Could there really still be one?”

Her voice trembled, eyes wide as she spoke. She fiddled nervously with her sari pallu, her stories taking on the weight of lived experience. Even the ticking of the old wall clock seemed to pause.

My uncle looked as if his soul had left him.

He sat on the edge of the charpai, staring into space, knuckles white.

“Ma, I really think that was it. The first time I saw it, I felt it wasn’t human. If you say it was a person, what would he be doing in the old jungle? Besides, in our town, is there anyone I don’t know? I’ve never seen that person. If you say he was a passerby, no one would go into the old jungle, right? From what I saw, it must be over seven feet tall.”

The logic was sound. In a town where everyone knew everyone, a stranger was cause for alarm, especially in the old jungle.

Just as we were talking, a sudden loud noise erupted.

The whole house jumped. My glass of milk nearly toppled off the table.

“Bang! Bang! Bang!”

From the direction of the panchayat head’s house came the sound of skyrockets.

“Oh no, my baba!” my uncle shouted, rushing out.

He sprang up, forgetting his fear, his slippers slapping against the cool stone floor.