Chapter 4: Footsteps and Fingers

Dadi grabbed my uncle. “Don’t go out yet. It might not have been your baba who set those off. Lots of families in the mohalla have those skyrockets.”

She yanked him back by the sleeve, her gold bangles clinking. Her voice was fierce, but her hands trembled.

My uncle said, “Who would set off skyrockets at this time of day for no reason?”

He peered out the window, trying to spot any movement through the fog.

Dadi replied, “You can’t be sure. If you run out like this and run into Bhoot Baba, you’ll be sending yourself to your death. How did you get out of the jungle just now?”

She looked at him intently, as if searching his face for some clue.

My uncle said, “I crawled out. I left four-footed prints on the ground. It’s just a beast—it won’t recognise them as human.”

He tried to sound confident, but his voice shook. He wiped his hands on his kurta, eyes darting.

Dadi breathed a sigh of relief. “That’s good. When Bhoot Baba comes out of the jungle, it’s always led out by people. Today you crawled out. If it can’t tell you were human, it won’t follow you out.”

She folded her hands in silent thanks to the family gods, looking upwards for a moment.

I thought for a moment and said, “Dadi, that’s not right. He did come out. He was following behind us.”

My throat went dry. I could still feel the sensation of being watched, the chill clinging to my skin.

Dadi’s face turned pale. “You really saw him come out of the jungle?”

Her lips quivered, and she clasped my shoulder tightly, as if afraid I’d vanish too.

“I saw him. He was not far behind us.”

I nodded slowly, still unsure if my eyes had played tricks on me.

My uncle was startled. “Behind us?”

His eyes widened, and he looked at Dadi, then at me, like he’d just swallowed a mouthful of ice water.

I said, “Yes, he even waved at me—seemed like he called out to me too.”

The memory made my stomach twist. The voice in the mist was hoarse, like someone trying to speak through a throat full of gravel.

My uncle’s face lost all colour, and he collapsed onto a plastic stool.

He slumped, his hands clutching his knees, breathing heavily as if he’d run a marathon.

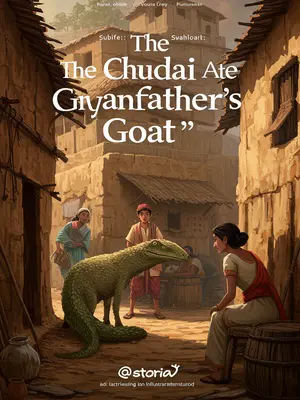

“It’s over. If it can stand on two legs and speak, it’s become a chudail. Whoever it targets, that family is doomed.”

His words sent a shiver through the room. Everyone grew silent, even the wall clock’s ticking sounded ominous.

Dadi hurriedly asked, “Did you answer when he called you?”

Her voice was urgent, eyes wild with fear, as she gripped my arm.

“Chachu wouldn’t let me make a sound. And his voice was raspy and scary, so I didn’t answer,” I said.

I could barely get the words out, my hands shaking in my lap.

Dadi quickly had me take off my red sweater and put on black clothes.

She rummaged through the trunk, grabbing my old black shirt and trousers. “Jaldi, beta!” she urged, helping me change with trembling hands.

I asked why I had to change clothes.

My voice was muffled by the black sweater as I pulled it over my head. Even changing didn’t make me feel safer.

Dadi said, “Once Bhoot Baba targets someone, he won’t stop until he eats them all. If you didn’t answer, he can’t remember your voice. If you change your clothes…”

She left the rest unsaid, but the implication hung heavy in the air.

Before she finished, we heard heavy ‘dhap-dhap’ footsteps outside the courtyard wall.

The sound reverberated through the ground, each thump louder than the last. The old dog sleeping outside whimpered and slunk under the verandah.

You could tell it was something big and alive.

Every step seemed to make the air shiver, and I felt a cold wind brush past my ears, though every door and window was shut.

Dadi and uncle exchanged a glance.

There was a silent agreement in their eyes: protect Sonu at all costs. Dadi pressed her palms together in a quick, desperate prayer.

They quickly ran back into the house and bolted another door.

The house now felt like a cocoon, layers of doors between us and whatever waited outside.

Dadi whispered, “Sonu, this isn’t good. Call the panchayat head and see if your baba made it over there.”

Her whisper was sharp, urgent, as if afraid the very walls might be listening.

My uncle hurried to call the panchayat head’s house.

He dialled with trembling fingers, the old black phone’s rotary dial making a shuddering whir.

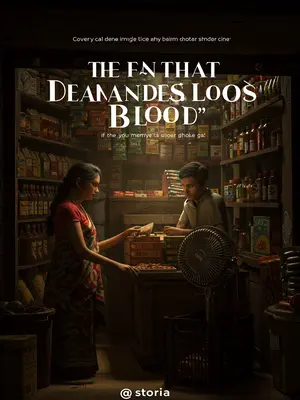

Back then, it was just a few years after the reforms, and pagers were rare. Everyone relied on landline phones to keep in touch. The panchayat head’s house was for officials, ours was the little kirana shop. Only our house and the panchayat head’s had phones in the whole mohalla.

The shrill ring of the phone echoed in the silence. Even the tick-tock of the clock seemed to pause, listening.

My uncle called, and the phone at the panchayat head’s house rang for a long time, but no one answered.

He frowned, sweat beading his brow, fingers drumming the table impatiently.

My uncle’s hands were shaking. “There’s no way the panchayat head wouldn’t answer the phone at this time.”

He bit his lip, glancing at dadi for reassurance.

Dadi said, “Call again.”

Her voice was tight, her grip on my shoulder growing stronger.

My uncle dialled again. Still no answer.

He banged the receiver on the cradle, muttering under his breath.

Even dadi began to doubt. “That’s impossible. Even if the panchayat head isn’t home, his wife should be. Isn’t it time to make lunch?”

She checked the clock, then the window, as if expecting to see someone walk past.

At this moment, the ‘dhap-dhap’ footsteps passed by and then came back.

Each step seemed heavier than before, as if whoever—or whatever—was outside was circling, searching for a way in.

They stopped right at our courtyard gate.

The latch rattled softly, and the gate creaked as if it might give way. I clung to dadi’s sari, heart hammering.

I could feel something peering inside through the crack in the door.

A chill ran down my spine, and the urge to cry pressed up behind my eyes.

The hairs on my body stood on end.

My arms prickled with goosebumps, and I bit my lip to stop from whimpering.

“Thak thak thak.”

The courtyard door was knocked on.

The sound was deep and deliberate, not at all like our usual visitors who rapped lightly, calling out from the lane.

Dadi’s arms trembled as she held me.

She pressed me close, her heartbeat loud in my ear.

My uncle grabbed a sickle and stood behind the house door.

He looked almost comical in his fear, brandishing the rusty old sickle, but I could see his hands shaking.

The three of us didn’t make a sound.

We barely breathed. Even the mice in the kitchen seemed to go silent.

After a few seconds—

“Thak thak thak.”

The door was knocked three more times. The sound was even heavier.

My uncle braced himself and shouted, “Kaun hai?”

His voice came out hoarse, bravado barely covering his terror.

“Main hoon.”

My dadaji’s voice.

Relief rushed over me, and I nearly cried out, “Dadaji!”

I exclaimed in delight, “Dadaji is back!”

I nearly jumped out of dadi’s arms, desperate to see him.

As I spoke, I wanted to rush out and open the door.

The urge was overwhelming. My feet found their way to the door almost by themselves.

Dadi pulled me back. “That’s not your dadaji.”

Her grip was iron. She glared at me, her eyes wide with terror and certainty.

“But that’s really dadaji’s voice,” I said.

I struggled, not wanting to believe something so sinister could imitate his warm, gruff tone.

My uncle said, “It’s my baba’s voice. I can’t mistake it.”

He looked at dadi, torn between hope and dread.

As he spoke, he was about to pull back the bolt.

His hand hovered over the latch, uncertain.

At this moment, dadaji’s anxious voice came from outside, “Open up quickly. Bhoot Baba came out of the jungle!”

The urgency in his tone was unmistakable, exactly the way dadaji would call if something went wrong.

My uncle pulled back the bolt on the house door and went to the courtyard to open the main gate.

He moved fast, as if his heart had already decided, but his eyes were wild with confusion.

Dadi grabbed him hard and whispered, “Munna, Munna, don’t go. That definitely isn’t your baba.”

Her voice cracked with desperation. She looked at him the way only a mother can: fierce, terrified, protective.

As uncle’s hand closed on the latch, the air outside grew impossibly still. Was it really Dadaji—or something else waiting to come in?