Chapter 1: The Day Everything Changed

E resemble all those bad Nollywood films, but this one na real life—no camera, no director. Students, lecturers, family members, even one famous performing artist—all of them become victims. After that day, the air for the institute no ever remain the same. Whispers dey fly everywhere, even the tall mango trees for courtyard bend ear as if dem dey listen to the tori wey no wan die.

The National Film Institute na big centre for arts, dey raise filmmakers wey dey shine for Nigeria and abroad. Harmattan dust dey hang for air, turning everybody’s lips white.

If you ask anybody for Plateau, dem go tell you say the National Film Institute na the pride of Jos—where dream dey born and stars dey grow. From old men for Terminus Market to pikin wey dey hawk zobo for gate, everybody sabi the name. Even for harmattan morning, when cold dey bite finger, students still dey rush enter class, eyes full of hope.

If you waka go the east side of the teaching area, just north of Jos Film Studio, you go see the staff quarters.

Those staff quarters stand gidigba, painted cream and green, with old balconies where women dey gossip for evening and children dey chase themselves for cracked staircase. Sometimes, breeze go carry scent of akara and burning firewood from canteen reach there.

Na for afternoon, July 6, 1994, just pass 4:00 p.m., bad thing happen inside one of those high-rise apartments for staff quarters.

That weather, sun no too strong but ground still dey hot. You fit hear okada noise, and small boys dey laugh play table tennis for downstairs. But upstairs, wahala dey cook—nobody sabi say e dey come.

Jumoke, pikin of the popular actor Okechukwu Nworie, come back from school with backpack for shoulder, enter her building hallway.

Jumoke na Lagos pikin, but her papa big for Jos, so she get street sense and sabi greet elders well. She just finish from St. Louis College, sandals dey bite her leg, so she dey drag foot small-small. The zip for her bag dey jingle for the quiet corridor.

As she commot from elevator for seventh floor, she just know say something no pure.

Her heart miss one beat. That floor dey always peaceful, cold pass other ones. But today, na silence everywhere, and sharp smell dey her nose. She hear her own breath loud, and the smell of old mop water mix with something bitter.

The iron security gate wey dem dey always lock stand wide open.

E never happen before. Jumoke pause, hand for railing. She peep right and left like rat wey see cat shadow. She dey wonder who forget lock gate. Na Jos, not Lagos, but people dey careful.

As she waka reach her apartment, Jumoke body dey tell am say wahala dey.

She slow down, as if she fit disappear inside wall. The corridor empty like say everybody travel. Her shoes heavy, every step sound for her ear like drum.

No be only the iron security door, even the wooden inner door dey small open.

Her chest tight. For their house, security na serious matter. Wetin fit make both doors dey open as if dem dey do party?

Wetin fit don happen?

She mutter under breath, “God abeg o.” She remember Mummy’s warning—“If you see anything wey no pure, no enter!”—but her hand still dey shake as she push. Courage still carry her leg go front.

Normally, both doors suppose lock. But now, faint metallic smell—like blood—hang for air.

The scent choke her, mix with that smell of Dettol and Omo from mopped floor. She remember how film dey show blood, but she never believe say she go smell am live.

Even as small girl of ten, Jumoke don see things because her parents be celebrity. She strong, but this one different.

She remember all the times wey she follow Mama go film set or Papa act village chief. But this one no be acting, her hand dey shake as she push the door gently.

She push the wooden door open, enter softly. Wetin she see freeze her for spot.

Her throat lock up. Curtains dey move small-small with Jos breeze but e no comfort her. Television off, everywhere too still. She wan shout, but her mouth dey dry, like when NEPA take light for middle of film.

Her mama, Amara Nworie, lie for her side inside parlour, back face door.

At first, the wrapper wey Mama tie almost cover her whole body, just like when she dey rest after dance class. But today, her fingers no move, gele scatter for ground beside her head.

Amara Nworie na dancer. She dey do splits and backbends anyhow. Jumoke first think say, “Mummy dey practice again?”

She wan talk say, “Mummy, you don start again o!” but her voice scatter like cracked radio. Her leg glue for ground.

But as she waka near, cold pass her body.

Goosebumps full her hand. Ceiling fan dey whine overhead, tension just dey hang for air. Her steps slow, every one heavy like block.

Why Mummy go dey practice for normal clothes? And why everywhere quiet like burial ground?

She reason am: Mummy no dey ever dance without her workout tight or favourite ankara. Silence stretch so tey, even house rat no move.

Ah!

One sharp gasp escape her mouth. Her mind dey shout, “Run! Call for help!” but her tongue heavy like fufu wey no get soup.

Jumoke see big pool of blood under her mama, and more blood don soak through her belly, stain wrapper red.

She almost fall back, knees buckle, but she hold armchair. The blood thick, dark, spread wella, soak the white fluffy rug wey Mama just buy from Main Market.

Jumoke nerves wan cut. She rush her mama side, dey shake her.

She wan shout, but her voice scatter like cracked radio: “Mummy, wetin happen? Mummy, wake up!” Her small hand dey shake Mama shoulder, but na only coldness and stillness she feel. Tears dey gather for eye.

But Amara Nworie no respond. For hot Jos afternoon, her body don already cold.

Even flies don begin gather for wound edge. Her mama hand rest for ground, limp, like all the life don waka commot. The house dey choke with sorrow, spirit of pain hang for air.

Jumoke chest dey jam. Wetin she go do?

Her tongue heavy like fufu wey no get soup, throat dey scratch. She remember, “If wahala happen, call Papa.” But her legs dey shake like generator wey low on fuel.

Her papa, Okechukwu Nworie, dey away for film set. She need call am sharp-sharp.

She rush go parlour landline. The rotary phone old, but she sabi dial Papa number fast—she don use am beg for biscuit money before.

As she hurry go phone, her foot jam something for floor—gbam!

The sound loud inside parlour. She look down, heart pound like masquerade drum.

She look see say na bloodstained dagger.

Knife no small—like the one butcher dey use for abattoir. Blood still dey drip from tip, her hand begin shake again.

Thick, sticky blood stain her sandals.

She almost slip, but panic hold her chest like cold hand. The blood sticky, her blue sandals don turn red.

Fear scatter her brain. She grab the knife—hand shaking—then fling am outside, like say the evil go follow am comot. Her scream tear through the air, cut the quiet like broken bottle.

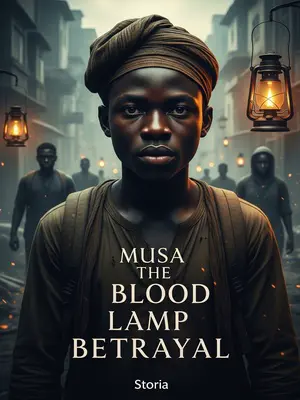

Na that time, Baba Musa, recycling collector for National Film Institute, dey ride his keke napep pass building.

He dey whistle one old Ayinde Barrister song, keke rattling over potholes. Sack of empty bottles dey for back, face full of sweat, dey complain how government no dey pay pension.

The dagger—over half a foot long—whistle pass him nose, land for ground with thud.

Baba Musa jump, shout, “Ah! Na who wan use knife pursue me for afternoon?” People for other compound begin point and shout.

He press handkerchief for head, bend down gently, eye the knife as if e go bite. “Na wah o, this world don spoil,” he talk.

Na real knife, blood full am.

Blood fresh, fear grip am like police hold thief. Baba Musa spit for ground, whisper, “Chineke, cover me o!”

“Ah ah, who wan kill me? Who dey craze like this, dey throw knife from window? If you get mind, come down explain yourself!”

One woman grab her chest, shout “Blood of Jesus!” Another begin dey pray loud, calling Holy Ghost fire. Children stop football, market women rush come. Even security man, Baba Sunday, forget gate work.

Jumoke poke head from seventh-floor window, voice shaking: “Uncle, sorry o—my mummy was stabbed with a knife…”

People look up, shock pin everybody. Next second, everywhere scatter—some rush inside, others shout, “Call police! Call ambulance!”

Nobody know say this na just the beginning—the real evil never show face.