Chapter 1: A Forgotten Prisoner

After I finished university in 2005, they posted me to the correctional education department of a men’s prison deep in the hills of southeastern Nigeria. I became a counselor—the one who gives last talks, offers advice, tries to help prisoners fix broken ways of thinking so they might find a path to change.

The prison, tucked into a valley near Okigwe, was always shrouded in mist each morning. The only sounds at dawn were the crowing of cocks, the distant ring of a church bell, and the steady gen noise humming like angry bees. I remember my first day—standing in my too-stiff shirt, clutching my posting letter and trying not to show my nerves as I passed by rows of high concrete walls topped with rusty barbed wire, watched by silent warders with heavy eyes. I was still young, thinking I could make a difference.

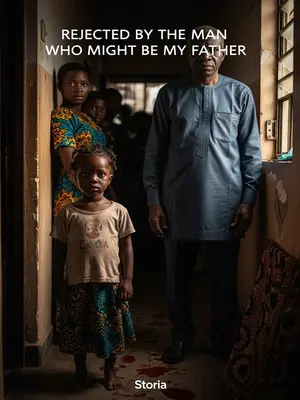

There was a prisoner called Ifedike. He wasn’t even one of my key cases. He got the death penalty with a two-year reprieve for murder, and he’d already served over a year. His behaviour was just normal—not too active, but obedient, never involved in any trouble. He was quiet, almost invisible among the different types of prisoners.

You know the kind—he could sit in a crowded room and you’d barely remember his face afterwards. Prisoners here come in all flavours: the ones who shout and make noise, the sly ones who play politics, the broken ones who cry at night. Ifedike wasn’t any of those. He’d quietly sweep the cell, queue up for food without pushing, keep his head down. Nothing remarkable, nothing to gossip about, and so, in a place built on stories, he was almost forgotten.

One afternoon, I watched as the queue for beans grew rowdy. One inmate shoved another. Ifedike simply stepped back, eyes lowered, waiting his turn. Another prisoner muttered, "That guy na ghost. Never fights, never talks." Ifedike just gave a small nod, collected his food, and melted away. That was his way—blending in, never drawing wahala. Soon enough, his silence became a kind of shield.

If he had just kept his head down for a few more months, Ifedike would have passed the reprieve assessment and had his sentence reduced to life imprisonment.

But then, something happened.

Not long ago, Ifedike suddenly attacked his cellmate in a violent outburst—one-sided, every blow meant to kill. In less than ten seconds, he beat the man to death. The warders on duty didn’t even have time to react.

The news ran through the cell blocks like dry season fire through bush. Even the inmates who claimed to be hardened men shifted uneasily. A year of good behaviour almost made people forget that Ifedike was a demon who once killed and dismembered someone. Only his sharp lawyer managed to secure him that reprieve.

Now, Ifedike faces the end he deserves. Committing another crime during the reprieve, and in such a serious way, meant the death penalty was sure.

After the verdict, we told him a day ahead. Ifedike learned that the last 24 hours of his life had already been planned out in detail.

Tomorrow, he could see relatives, take a proper bath, eat well, receive a last talk, then have his identity checked and be handed over for execution.

Ifedike showed a strange expression but didn’t say anything.

I asked, “Do you have any questions?”

“No.”

A single word, flat as the wooden bench he sat on. It was as if he had already traveled beyond words, to a place where nothing matters.