Chapter 6: The Root of Shadows

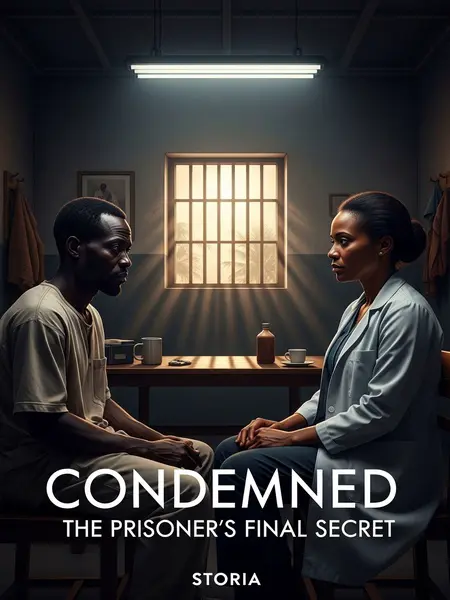

As a counselor, I know the mental states of most inmates here.

Some have wild mood swings and poor self-control, often needing my last talk. These ones are my main focus.

But as I said, Ifedike wasn’t my main focus. Since he came to prison, his behaviour was good, emotions steady, and I didn’t need to worry about him. Before this, I hadn’t talked to him much and didn’t know him well.

The murdered inmate, Musa Danladi, was in prison for molesting and killing a child—the lowest of the low, hated and bullied in prison, targeted everywhere. Because Ifedike was quiet and didn’t cause wahala, they put the two together, and they got along for quite a while.

Thinking about it, Ifedike didn’t really seem like someone who would kill over just a few words. But the facts are there.

I said, “Those murder motives were your own confession.”

“Were they?” Ifedike looked calm. “The story isn’t over yet.”

Execution was near. Did he still want to change his confession?

I checked the time.

“An hour and a half left. Go on.”

The generator outside sputtered, and I heard a warder humming an old Onyeka Onwenu tune as he walked past. Time was moving, even as it felt stuck here.

---

Ifedike’s narration (3):

To make me normal, my mother brought me to live near the execution ground for reverse education.

But after seeing too many executions, I got used to it; there were always just a few reactions before death, always the same kind of dying. I gradually felt the death penalty was nothing special.

Reverse education didn’t make me a good person. It only made me more comfortable seeing bad people die.

My mother didn’t know this. She still lowered her head every day to open that window for me.

Of course, my mother didn’t give up on positive methods.

There was a Dr. Yusuf who ran a chemist in town and also worked as a counselor. In those days, few people went for last talk, so he mostly treated small sicknesses like malaria and cough.

But I became a regular, getting advice and guidance from him.

To cover my treatment, my mother even started dating the fifty-something bachelor Dr. Yusuf, claiming it was so he could help raise me.

People in town laughed behind her back, saying her son was already grown, yet she still wanted a man.

She dated him anyway, but didn’t skimp on treatment fees. The counseling was expensive, and the drugs even more so. Since Dr. Yusuf wasn’t qualified to prescribe psychiatric drugs, he got them through back channels and prescribed them to me.

It’s not like we couldn’t go to a proper hospital for treatment and drugs, but my mother refused.

She kept all this secret because she didn’t want me to have a psychiatric record; she hoped I could be cured quietly, so my future wouldn’t be affected.

She trusted Dr. Yusuf’s skills and always believed I still had a future.

It was because of my mother that I never had any psychiatric records.

Dr. Yusuf believed my antisocial behaviour was caused by childhood trauma. He said hypnosis could find my psychological shadow, dig out my hidden pain, and reshape my subconscious to cure me.

It sounded magical, but it never worked, not even once.

Because successful hypnosis needs trust. I couldn’t trust Dr. Yusuf, so he found nothing.

If you can’t cure the root, you just treat the symptoms. Dr. Yusuf gave me strong medicine he brought from Onitsha, which helps calm emotions and suppress criminal urges.

But this medicine has strong side effects: it makes people dull, sleepy, and causes thinking problems. He prescribed it anyway, but I never took it. So neither the root nor the symptoms were treated.

This didn’t affect Dr. Yusuf; if he couldn’t cure me, I’d always be his patient. In the end, I just went to his chemist to eat snacks and read books, truly living up to the ‘help raise the child’ excuse.

Dr. Yusuf and I fooled my mother; only she was kept in the dark.

To pay for my expensive treatment, my mother not only worked at the factory, but also did several side jobs. She wasn’t even forty then, still looked young, but half her hair was already white.

Sometimes at night, I heard my mother crying and sighing; sometimes I saw her full of hope, always busy.

My father saw my true nature and left decisively; but my mother was stubborn and refused to give up.

Many women are like that; even if they can survive on their own, deep down they still want someone to lean on.

She had only one son left. She saw a future in me and put all her hopes on me. She wanted me to be like everyone else: go to school, work, get married, have children, and hoped to depend on me in old age.

She didn’t do anything wrong; she was just a normal mother.

But I was not a normal child.

I couldn’t meet my mother’s expectations; I felt suffocated and pained around her.

School, work, marriage, children—none of those were what I wanted. The only thing I craved was crime; that was my destiny.

You might wonder why I was so sure I’d become a criminal.

Because that’s what I realised after trying to save myself.

My time at the chemist wasn’t wasted. I read through Dr. Yusuf’s psychology books and discovered the solution was inside.

Childhood trauma has a butterfly effect, affecting a person’s whole life. That’s the terror of childhood shadows.

My change from a good child to a bad one could actually be traced.

Before, I deliberately avoided that experience, which made me suffer for years.

After self-studying psychology, I gradually understood: if the knot from childhood trauma isn’t untied, I’ll always be in pain and never be free.

In primary two, I locked a classmate in a store and watched people search for him. But I had no beef with that classmate; the one who hurt me was his father.

His father was called Zachary Ozo.

Zachary Ozo molested me—a boy of seven or eight.

At that age, I didn’t understand much, but seeing a kind adult suddenly become a monster was real, and the fear and pain I felt were real.

Afterwards, I was very scared and told my father, hoping he’d help me get justice. But my father hesitated and just told me not to go to that classmate’s house again.

If my father didn’t dare face him, I dared even less. Unable to let out my pain, I could only take revenge on Zachary’s son.

Ordinary revenge didn’t hurt him at all. I only locked his son in a store, and he molested me again, warning me not to touch his son again.

All along, Zachary Ozo was a gentle, kind man, nice to everyone, always smiling.

The first time he saw me, he smiled and said, “This child is so lovable,” and bought me plenty of biscuits.

But in the end, he showed his most terrifying face to me.

No one would believe a child’s accusation against a good man, not even my father.

After that, I never mentioned it again, but I became sensitive, gloomy, and vengeful.

Even for small things, I’d go all out for revenge. Every act of revenge was like trying to make up for the regret of not being able to fight back the first time.

But it was like trying to quench thirst with empty calabash—never enough.

I gradually realised that Zachary Ozo was my real knot. No one could save me but myself.

I had to kill him.

I started planning to kill Zachary Ozo ten years ago. When I was small, I couldn’t fight back; now I’m grown, he’s old, and killing him is as easy as killing a fly.

You say I destroyed Zachary Ozo’s happy family. Why not say he destroyed my whole life?

Only by killing him could I be free.

That is the real reason I killed Zachary Ozo.