Chapter 2: The Vanishing

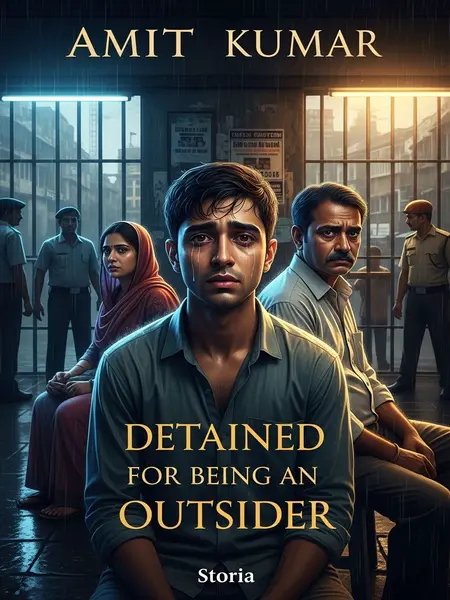

What exactly happened to Amit?

The question gnawed at everyone. Even as they sat in the waiting room, cups of watery hospital chai growing cold, the family replayed every possible scenario. Mistaken identity? A petty quarrel gone wrong? No one knew. Every scrap of information, every whispered rumour, was clung to like a lifeline.

For a long time after his death, the family and friends only knew that Amit had been detained. Even his experiences after detention were pieced together from friends’ memories, building a blurred outline.

The story came in fragments—a phone call here, a text there. Amit’s friends, many from small towns, swapped stories in hostel corridors and WhatsApp groups. It was like doing a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces. Ramesh kept a notebook, scribbling every detail, determined not to let any clue slip away.

At 10 p.m. on 17 March, Amit left his rented flat to go to a cyber café. He’d only been in Mumbai for a little over twenty days and hadn’t got the temporary tenant registration. He didn’t even take his Aadhaar card when he stepped out.

That night, Mumbai buzzed as always—rickshaw horns, street-side dosa sizzles, the distant rumble of trains. Amit told his roommates he’d just check emails at the cyber café. Like many new arrivals, he hadn’t figured out all the paperwork. The flat was cramped, filled with Maggi’s masala scent and too many slippers at the door. His Aadhaar was tucked away in his bag, forgotten in the rush.

He encountered police doing ID checks everywhere. After questioning, officers took him to Andheri Police Station. At 11 p.m., Amit called Mr. Joshi, his roommate, from the station, asking him to bring his Aadhaar and some money for bail.

Mumbai police had been doing routine checks for weeks. Amit’s bad luck brought him to their notice. The officers were curt, their tone making it clear—no arguments. In the harsh station light, Amit’s fear grew. When he managed to call Mr. Joshi, his voice trembled. “Bhai, jaldi aa jao. Aadhaar aur kuch paise le aana. Police ne rok liya hai.” Joshi, usually calm, felt panic rise. This was not the kind of trouble you could talk away.

Around midnight, Mr. Joshi reached the police station, but the police refused to release Amit, saying, “Nahin, isko nahi chhod sakte. Orders hain.” Mr. Joshi saw Amit and asked through the window what happened. Amit replied he had answered back to the police.

Joshi waited for hours, trying to reason, but the officers were unmoved. “Procedure hai, boss. Kuch nahi ho sakta.” When Joshi finally saw Amit through the iron-grilled window, his friend’s eyes showed fear and confusion. Amit’s voice was barely a whisper. “Maine sirf jawab de diya tha… woh gussa ho gaye.” Joshi tried to reassure him, but deep down, he knew things were slipping away.

Mr. Joshi had no choice but to leave. He never saw Amit again.

Defeated, Joshi walked out, mind racing with what-ifs. The city outside felt suddenly hostile—every auto, every chaiwala, every police post a threat. He checked his phone again and again, hoping for some word. But there was only silence, broken by the clang of the station gate shutting behind him.

On 18 March, Amit was sent to the Mumbai City Detention and Repatriation Transit Centre. There, he managed to call another friend. That friend remembered Amit speaking quickly, stuttering, terrified.

The detention centre’s rules were harsher. Amit’s call was rushed, desperate. “Yaar, kuch kar. Bahut darr lag raha hai.” His words tumbled out, as if he was afraid time would run out. The friend tried to ask questions, but Amit could barely finish a sentence. Other voices echoed in the background—shouting, crying, the clatter of steel plates. The place felt built to erase people, not protect them.

On the 19th, the friend tried to visit the centre to bail Amit out, only to find he’d already been sent the previous night at 11:30 p.m. to Sion Hospital, more than an hour away, which doubled as the Mumbai Detained Persons Medical Aid Centre. Hospital staff told them only family could post bail.

The friend rushed across the city, fighting crowds and traffic, clutching documents and silent prayers. But the staff were curt. “Sirf parivaar dekh sakta hai. Aap friend ho toh kuch nahi ho sakta.” It was a dead end—no explanations, no hope, only a growing dread that something terrible had happened.

On the 20th, the friend called again to ask how to get Amit released. This time, the answer was unimaginable—Amit was dead.

The words landed like a blow. “Amit ab nahi raha.” The friend was stunned, unable to speak. He didn’t know how to tell Amit’s family, or what to say. For a while, he stood outside the hospital, watching vendors hawk chai, doctors rush past, kids play cricket nearby. Life went on, but for Amit’s family, everything had stopped.

How could a living person just die?

The question haunted everyone. In Rajpur’s lanes, in college corridors, in cramped Mumbai rooms, people asked it again and again. Mothers hugged sons tighter, fathers called home more, friends whispered theories late into the night. “Itna accha ladka, bina wajah… aisa kaise ho gaya?”

In the days after, the family visited the police station, the detention centre, hospital, district magistrate’s office, court, city municipal office, social welfare department, and health department. A few rural people, strangers in the city, spent days running from office to office—and gained nothing at all.

Every office was a new maze—endless counters, files stacked high, peons shuffling papers with studied indifference. “Yahan mat jao, wahan jao.” At every step, they met shrugs, excuses, or open hostility. They carried homemade thepla and thermos flasks, huddling in hospital corridors, clutching Amit’s photo and piles of paperwork. The city felt colder, more alien. Their Haryanvi accents drew curious glances from nurses. One attendant muttered, “Gaon wale hain, kuch samajh nahi aata.”

They went to every government department they could, but no one gave them an answer. Only more doors, more silence.