Chapter 2: Clash at the Borders

In the spring of 1762, the Burmese army arrived.

The first reports came with the April rains. Messengers arrived breathless at the Bengal nawab’s court, their dhotis muddied, eyes wild, bearing tidings of Burmese banners unfurling at the eastern passes. Where once there had been only scattered tribes and petty rajas, now there marched disciplined regiments with European guns gleaming beneath the mango trees.

They directly collected the so-called "Huama tribute" from the local rajas and zamindars along the Assam border, and, in addition, ruthlessly plundered people and wealth.

Zamindars in their white muslin angrakhas wrung their hands, forced to hand over chests of coin and sacks of rice to the Burmese tax collectors, who spoke in strange accents and bore the scars of jungle fighting. To refuse, even to hesitate, was to see one's own fields set alight, or one’s children carted away across the hills.

At that time, the Mughal garrison on the India-Burma border was very limited—basically only a few sepoys stationed along the so-called "Eight Passes of Imphal," with no more than 500 men in total.

The border outposts were nothing but sun-baked mud forts, where sepoys dozed in the shade and the only sound was the creak of bamboo in the wind. Facing the full might of the Konbaung army, these small detachments were as helpless as goats before a tiger. Letters sent to the nearest Mughal subahdar begged for reinforcements, but the roads themselves were soon too dangerous for even a single rider to cross.

As a result, from then on, the Burmese treated India's Assam border region as their personal "cash machine," raiding it at will.

The villagers, meanwhile, developed their own warning signals: a series of drumbeats that travelled from hamlet to hamlet, warning of approaching raiders. Fields lay untended, and the markets grew empty as word spread—today it is Manipur, tomorrow perhaps Silchar. The borderlands became a place of fear, where the sound of a distant conch shell at dusk could send families scurrying into the forests.

Naturally, this attracted the attention of the Mughal central court in Delhi.

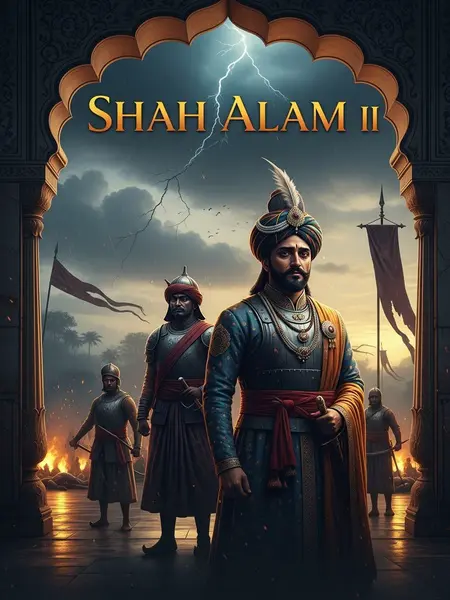

On a sultry May evening, as peacocks called from the gardens and the Emperor’s musicians played ragas in the marble halls, Shah Alam II’s viziers pressed before him the letters from the east. Their brows were furrowed, the air thick with the scent of rose attar and worry. The Empire’s pride had been pricked—Delhi could no longer ignore the insult.

In 1765, Shah Alam II ordered the Nawab of Bengal and Assam, Mir Qasim, to launch a counterattack.

The news passed quickly through the corridors of power: Mir Qasim, known for his quick temper and shrewd mind, would gather the banners of Bengal and Assam. In Murshidabad, the palace lamps burned late into the night as officers gathered around maps, the air electric with the prospect of battle.

With imperial orders, the response was swift. The Bengal Mughal army quickly assembled 3,000 troops and launched the first large-scale counteroffensive against the continually invading Burmese.

For the first time in years, the old arsenal at Rajmahal echoed with the clang of sword against shield, the fletchers worked double shifts, and the sepoys stood taller in their uniforms. Mothers tied black threads around their sons’ wrists, murmuring ancient mantras and pressing a pinch of turmeric behind their ears for protection as the imperial army marched out to defend the land’s honour.

The two sides fought fiercely near the territory of the local chieftain (modern-day Silchar). The result: the Mughal army was defeated, suffering 600 casualties.

The earth was soaked with blood, and for days afterwards, the vultures circled lazily above the broken fields. Survivors spoke of musket fire that never seemed to end, of Burmese war drums beating louder than their own hearts. For the proud Mughal battalions, it was a bitter defeat, and the news carried back to Delhi like a monsoon storm.

When news reached Delhi, Shah Alam II was furious. He summoned his trusted general, Nawab Faizullah Khan, and ordered him to carefully plan a new counterattack.

In the red glow of evening, Faizullah Khan bowed before the Emperor, his jaw set in determination. “Give me leave, Huzoor,” he vowed, “and by Allah, I shall return with victory or not at all.” The court watched, some with hope, others with silent dread—already whispers began that the Burmese were unlike any foe they had ever faced.