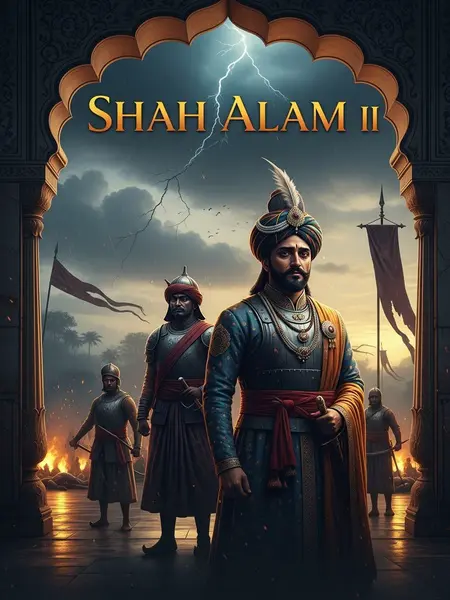

Chapter 4: The Gathering Storm

After this, Shah Alam II decided to escalate the conflict massively—from a border skirmish to a war of annihilation. If there was to be a fight, he would see it through to the end.

From the minarets of Delhi to the tea gardens of Assam, word spread: the Emperor had thrown down the gauntlet. In every mosque and temple, the prayers took on a new urgency, the old dream of Mughal supremacy rekindled in the hearts of many. "Let it be war, then," the nobles said, their voices grim with resolve.

Early spring 1769, March. In Delhi, thunder rolled over the Red Fort, and torrential rain poured down without end.

The Red Fort itself seemed to shake as the rain hammered its ancient stones. Lightning split the sky, and for a moment, the whole city was lit up—shopkeepers rushing to pull down their shutters, children shrieking as the power flickered, the very elements seeming to echo the storm gathering within the Emperor’s heart.

The enraged Emperor Shah Alam II personally directed the counteroffensive against Burma for the first time. He meticulously reviewed all historical records on Burma and ordered his officials to gather intelligence through every available channel.

Within the palace, clerks scurried from archive to archive, their ink-stained fingers trembling as they copied ancient reports and foreign treatises. The Emperor’s spies, disguised as traders and fakirs, were sent eastward with orders to return or not return at all. No detail was too small—who supplied the Burmese, how did their generals command, what omens guided their king?

He finally realised that Burma was not the "small state" he had imagined. Even Siam (Thailand), the great Southeast Asian nation that had long paid tribute to the Mughals, had already been destroyed by Burma. Burma had long been the overlord of Southeast Asia.

The realization hit the court like a slap: all their old assumptions were dust. The empire’s scribes noted grimly that the days of easy conquest, when the mere name of Hindustan brought submission, were long gone. Now, it was the Burmese who inspired tribute, the Burmese whose armies moved like a force of nature across the map.

Moreover, most of the regular Burmese army was already equipped with "Western self-igniting guns" (European flintlock muskets).

The Emperor's arms merchants muttered darkly over their ledgers, seeing the threat for what it was: the days when Indian swords could win against tribal spears were finished. The matchlock and the flintlock ruled the day now, and those who lagged in armaments lagged in fate.

Fine, if that's how it is, then don't blame me for being ruthless. I will get serious.

Shah Alam II’s resolve hardened. “Tell the world,” he declared to his gathered ministers, “that Delhi is not finished. If the Burmese want war, let them choke on it.” The old warrior spirit of Hindustan, so long suppressed by politics and intrigue, now blazed forth in his eyes.

In April, he appointed the empire's top minister, Grand Vizier Asaf-ud-Daula, as the commander-in-chief for the Burma campaign, with overall authority over military affairs, and assigned the seasoned generals Haider Ali and Jai Singh as his deputies. He also assembled a host of the empire's fiercest commanders: Rana Amar Singh, Bahadur Khan, and others—all veterans from the border armies who had distinguished themselves in the Deccan campaigns.

The summons went out from the Diwan-i-Am, and soon, from the palaces of Awadh to the forts of Jaipur, the names of great generals filled the air. Their arrival in Delhi was a spectacle: camels loaded with gifts, banners fluttering, and courtiers craning their necks to catch a glimpse of the new hope for the empire. In the evenings, under the soft yellow glow of lanterns, the war council plotted their moves over spiced wine and sweetmeats.

Furthermore, Shah Alam II did not hesitate to deploy the Mughal Empire's "hidden treasures"—four elite units, all first-rate forces:

1) Pathan cavalry—these were the Mughal Empire's top crack troops. Even the Rajputs trembled at the sight of them, and they were renowned as invincible throughout North India;

2) Artillery Corps—a specialised artillery unit established during Akbar's era, fully equipped with matchlock muskets and a complete array of field artillery;

3) Rajput cavalry—after the fall of various Rajput kingdoms, the remaining cavalry units were reorganised by the Mughal Empire. In terms of combat power, they surpassed most other regional cavalry;

4) Mughal cavalry—the Emperor's own elite troops, rarely deployed, known as the Shah's personal guard.

Asaf-ud-Daula inspected these units himself, standing in the early morning dew, his breath curling like incense as the Pathans displayed their horse-riding skills and the Rajputs raised their lances to the sky. Old veterans wept openly to see the empire’s finest assembled at last, and the bazaar-wallahs began hawking miniature clay horses painted in the colours of the elite regiments.

The total strength of these units was about 9,000 men. Some might ask, why not even 10,000? How could such a small force launch a war of annihilation? That is because they did not understand the combat effectiveness of these Mughal elite units.

In the sabhas of Delhi, learned men argued deep into the night: “What is the value of a lakh of common men next to a handful of true warriors?” The answer, for the moment, was hope. Hope that these 9,000, forged in the fires of old Hindustan, could succeed where so many others had failed.

To be frank, any one of these four units represented the pinnacle of military power in South Asia at the time.

The very mention of the Pathans or Rajputs sent a thrill through the soldiers. Children played at being Mughal horsemen in the alleyways, and old men recounted tales of the artillery’s thunder shaking the ground from Gwalior to Hyderabad. This was not just an army—it was the living heart of a civilization refusing to die.

Yet Shah Alam II was still not reassured. He dispatched the "Mughal special forces"—the Barha Sayyid Battalion.

These were not mere soldiers; they were legends in their own right. The Barha Sayyids, with their proud topknots and fierce eyes, had earned their reputation in the darkest corners of the Deccan. Mothers frightened their children with tales of their stealthy attacks, their swords flashing in the moonlight.

The training of the Barha Sayyid Battalion was completely different from that of ordinary cavalry, infantry, or artillery. Swordsmanship, firearms, hand-to-hand combat, and formations were all basic for them; their true specialty was one thing: assault and killing.

In hidden courtyards outside Ajmer, young Sayyids practiced night after night, the clang of steel and the thud of their bare feet on packed earth echoing through the hills. Their discipline bordered on fanaticism—some said they would rather die a hundred deaths than surrender a single inch of ground to the enemy.

This was a crack unit that Shah Alam II had spared no expense to train, investing vast sums of silver, originally to storm the massive Maratha forts in the Deccan campaigns.

Whispers in the court claimed that the Emperor’s own treasury was half-emptied to outfit these men: French sabres, Persian armour, and the finest horses from Balochistan. Even the Emperor’s personal goldsmith was said to have crafted their badges of honour.

Because they were stationed near the Aravalli Hills for many years, they were also known as the "Aravalli Barha Battalion."

In Rajasthan, the very name inspired awe. Merchants would offer discounts to Barha troopers passing through their towns, and bards composed couplets praising their speed and ferocity in battle. The hills themselves, so often silent, now echoed with the gallop of their drills.

At the end of April, before Asaf-ud-Daula set out, Shah Alam II reinforced him with this elite force.

As the Barha Sayyids arrived, their banners streaming in the hot summer wind, the entire Mughal camp erupted in cheers. It was as though the old spirit of Hindustan had returned at last—a spirit of courage, unity, and desperate, glorious defiance.