Chapter 2: Memories Washed Away

If Caleb Jensen could turn back time, he’d have skipped the trip to the county office that day.

He probably would’ve stayed home, tending the hickory smoker out back, the scent of slow-cooked pork drifting through the yard, or maybe fixing the leaky kitchen faucet while country radio played in the background. But fate has a knack for dragging old secrets out of hiding when you least expect it.

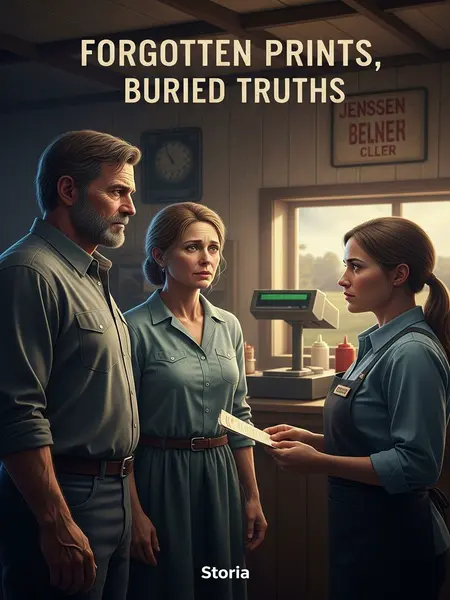

That spring was unseasonably cold. The radiators in the clerk’s office rattled and buzzed, sounding like a wounded animal. Caleb sat on a cold steel bench, nervously rubbing his hands, while I stared at the fingerprint scanner—until suddenly, the machine let out a piercing alarm, shrill as a tornado siren in the dead of night.

The sound bounced off the linoleum, making everyone in the waiting room jump. Even the janitor paused mid-crossword, eyebrows raised in alarm.

The case file from twenty-two years ago was stained yellow-brown, like a coffee ring on a manila folder left too long in a dusty cabinet.

The folder had that unmistakable musty, old-paper scent, the edges curled and brittle. History clung to it, heavy as a secret, every page thick with unanswered questions.

On that winter night, in the Harper family’s remote farmhouse a thousand miles away, four bodies were arranged in the moonlit living room, like stick figures posed by mischievous children. The son-in-law, Frank Miller, disappeared into the snowy darkness, leaving only a bloody thumbprint smeared on the frosted windowpane.

A full moon cast long shadows over the snowdrifts outside. That single bloody print became the only clue—a silent scream, frozen in time.

“Sir, your machine must be malfunctioning.”

Caleb’s Adam’s apple bobbed, as if he was trying to swallow a stone.

His voice trembled, the words stumbling out as if he barely believed them himself.

His wife slapped their marriage license onto the counter, the double-ring emblem on its plastic cover faded to bluish gray. “We’ve slept under the same roof all these years. If he’d killed anybody, don’t you think I’d know? Besides, twenty-two years ago he was only sixteen. When he came to us, he was as skinny as a fence post and wouldn’t hurt a fly—how could he kill anyone?”

She stood her ground, chin lifted in defiance, her accent twanging with Appalachian grit. She shot me a look like I’d accused her of cussing in church.

I stared at the perfectly matched fingerprint ridges on the comparison chart and remembered what the old county forensic doctor always said: “A fingerprint’s more reliable than any memory—it’s stamped on you for life.”

His words echoed in my head, but brought no comfort. The evidence was clear, even if the story was not.