Chapter 3: Death Row

The next morning, Arvind was shifted to the death row wing. As the psychological counsellor, I had to accompany him.

It’s a walk very few ever take—through iron gates, past the silent stares of guards and inmates, into a wing where the silence thickens with every step. The barracks here are painted a dull blue, the colour of forgotten mornings and dried tears.

Before execution, prisoners are allowed a family visit. But Arvind was an orphan—no family, no one to see him off.

The only person he’d ever written to was Neeraj Sinha, a male friend. Their letters, exchanged every two months, were always reviewed for content. At first glance, they were simple greetings—asking about each other’s families—but there was a subtle intimacy between the lines, something that set them apart from ordinary friends.

In the cramped mailroom, the staff would sometimes pause, a smile hidden behind a steaming cup of chai. One staffer whispered in Hindi, "Arre, inka rishta kuch alag lagta hai, yaar. Normal dost toh aise nahi likhte."

Speculation grew. But Neeraj never came to visit.

The latest letter, though, was from Neeraj’s wife. She’d noticed something and wrote to ask who Arvind was.

Only then did we learn Neeraj had recently married. We guessed this was the cause of Arvind’s sudden breakdown.

Now, shackled, Arvind dictated a final letter to Neeraj. It was the usual greeting, but with one final line: "No need to reply."

Even as he spoke, his lips barely moved, voice barely above a whisper. The warder holding the pen looked from Arvind to me, searching for words, but said nothing.

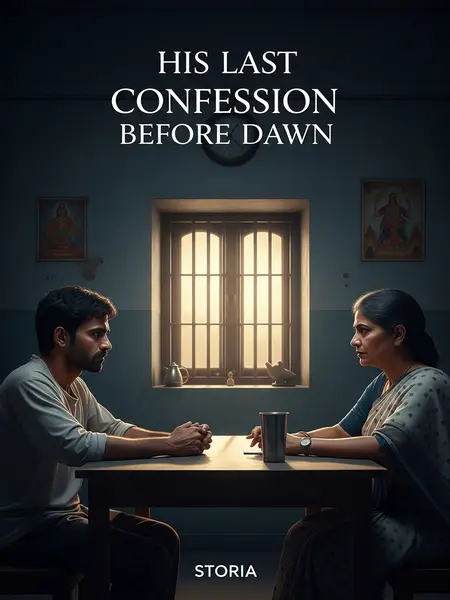

With two hours left, I entered Arvind’s cell for the last time.

He sat upright, calm, almost scholarly—yet the knife scars and burn marks on his face lent a fierce edge.

Most men in his position are broken by now, but Arvind seemed untouched by death’s shadow. There was a stillness in his gaze, like a temple idol: unmoved, inscrutable. I half-expected him to close his eyes and start a shloka, but he simply waited.

I said, "Arvind, do ghante baaki hain. You need to prepare yourself. Kuch kehna hai?"

He scoffed, "Abhi marne wala hoon, aur aapko meri mental health ki chinta hai? Faltu ki fikr hai."

"It’s a necessary humanitarian concern," I replied, though I suspected he truly didn’t need it.

"Dr. Mehra, suna hai aap TISS Mumbai ke topper the, ab yeh kar rahe ho? Kya talent ka waste nahi hai?"

His words caught me off guard.

He continued, "Maine bhi psychology padhi hai. Real psychology aisi bekaar nahi hoti."

I matched his tone. "Toh batao, tumhare hisaab se psychology ka asli kaam kya hai?"

He leaned back, pausing, then said, "Abhi toh marne ja raha hoon. Sab kuch mitti ho jayega, na? Feels like such a waste, this kind of ending. But still, I want to try one last time. Koi chance hai ki main kuch badal sakun?"

His words hung in the air, as heavy as a monsoon cloud, charged with tension.

"You still want to overturn the verdict?"

"How about I tell you a story, Dr. Mehra."

He straightened, tapped his foot, and looked me in the eye. I nodded. "That’s your right. I’m listening. But there’s not much time."