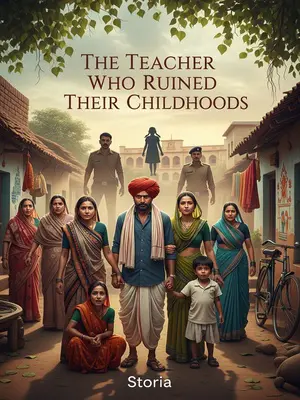

Chapter 3: Doubt and Trial

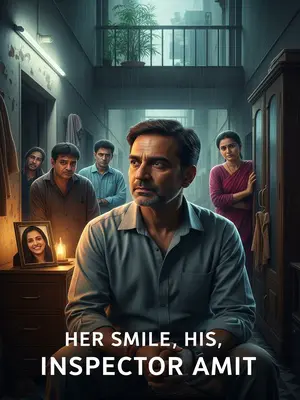

In my impression, Ramesh was a very responsible person. In all the years my daughter had taken the school bus, Ramesh had never once been late. I found it hard to believe someone like him would molest students.

The next morning, I sat on the balcony, sipping tea as the morning walkers circled below. I remembered how Ramesh would wait patiently for late children, how he once drove back to return a forgotten tiffin. The image of him as a predator jarred against everything I knew. Still, I couldn’t ignore what my daughter had said.

That evening, I called my daughter to my room, closed the door, and sat her down on the bed. The ceiling fan hummed overhead as I tried to keep my tone gentle. "Beta, Papa wants to talk to you. No scolding, just tell me clearly, okay?"

“Tell me, what number were you when Ramesh touched you? Who was before you? Who was after?”

I asked everything—where she sat, who got off first, did anyone see. My voice was steady, but my hands clenched beneath the bedsheet.

She hesitated, unable to answer. I pressed her softly but firmly, "Beta, tell Dad, sach sach bolo. Did Ramesh uncle really touch you? Or... is there something else?"

She fiddled with her dupatta, mumbling half-answers, eyes glued to the floor. The longer she hesitated, the more suspicion crept in. Finally, she burst into tears. My wife rushed in, furious, "Are you mad or what? You think your own daughter will lie about something like this? Bas karo! We should support her, not doubt her!"

“Whether Ramesh is innocent is for the police to decide. What does it have to do with us? At worst, we just apologise to him.”

Meera’s tone was final, hands pausing for a moment as she folded a towel. "Jo bhi sach hai, police will find out, na? Our job is to stand with our daughter. Agar galti hui, we will say sorry. But don't break her trust in us, please."

I was speechless, but she wasn’t wrong. The police are more professional than we are—they wouldn’t wrongly accuse a good person.

I looked at my daughter, her face streaked with tears, and thought, maybe Meera is right. Sometimes, it’s better to let the system do its job.

The police checked the school bus’s CCTV and GPS. They confirmed Ramesh drove as per regulations that day. Unless he could molest students while driving, there was simply no time for the crime.

The footage was grainy, showing only the backs of children’s heads as the bus jolted over potholes. The GPS printout had a red traffic police stamp. The inspector explained, “Saab, no stop, no delay. He followed the route exactly. Unless he has some magic, not possible, sir.”

Still, the police conducted forensic tests. No fingerprints, but a small amount of DNA—so intimate contact couldn’t be ruled out.

The forensic team in white overalls looked out of place among the dusty files and chai glasses. The DNA report was technical, but the phrase "intimate contact not ruled out" weighed heavy in the air. Mothers whispered, confused and afraid.

The police issued an ambiguous conclusion: “No direct evidence of molestation was found.”

The inspector read it out with a tired sigh. Some parents exchanged nervous glances. Meera’s lips pressed together, her folding paused for a second.

As soon as this result came out, the parents were furious. Complaints flew to the MLA, women’s commission, even the press. WhatsApp groups exploded—"Yeh police toh kuch nahi karti!" "Let’s talk to that reporter from Kaveripur Times, she’ll write a good article!" The collective outrage of colony parents is a force of nature.

A few hours later, the police changed their statement: “It is impossible to rule out the suspect’s possibility of committing the crime.”

The phrasing was classic bureaucracy—roundabout, careful, but loaded. Someone read it aloud twice, just to be sure. The parents nodded grimly. "Ab dekho, something will happen," someone said.

Although the two statements were nearly identical in meaning, the effect was completely different, because the prosecutor’s office opened a case based on the second statement.

The entire mood in the colony changed overnight. Uncles at the chai stall now debated legal matters. There was a new buzz—a sense that justice, finally, might be done.

Given the number of victims and the fact that they were all girls, the prosecution recommended the maximum sentence—seven years.

The newspapers the next morning carried the headline: "Kaveripur School Bus Driver Faces Jail for Molesting Five Girls." Aunties cut out the article, folded it into their purses, and it became the talk of the colony park.

The case went to trial quickly. Ramesh brought two witnesses: his former company commander, who testified to Ramesh’s discipline, and his mother, Sushila Devi.

The court was crowded, the AC humming weakly. The old army man in olive-green uniform said, "Ramesh Yadav was always honest, always dutiful. He saved two villagers during the floods in 2013. Such a man cannot do this."

Sushila Devi, frail in a white saree, wept as she folded her hands before the judge. "Mere bete ne kuch nahi kiya, saab. He brings me medicines, cooks for me, does pooja every morning. Please, have mercy."

After Sushila Devi’s plea, the courtroom fell silent. The judge adjusted his glasses, a peon offered water, and the crowd murmured, "Hai Ram." The emotional weight pressed down on all of us.

But their evidence could not change the outcome. After all, only God knows what really happened that afternoon.

In the end, the court found Ramesh guilty of molestation and sentenced him to five years in Tihar Jail at the first trial.

The gavel came down with a dull thud. The courtroom murmured in satisfaction. I felt an odd emptiness—relief, but also something unsettled.

Ramesh appealed. The parents felt the sentence was too light and were full of complaints. The fight was not over.