Chapter 1: Rotten Relations

The man running our school canteen—just because he’s the principal’s relative—treats us students like we’re invisible. His smug smile and that big belly shaking while he yells at the helpers, always makes my blood boil. The second we walk in, he glares at us as if we’re beggars crashing his palace, like our parents haven’t paid the hefty fees that fill his own relatives’ pockets. Sometimes, when he barks at us in the corridor, it takes everything not to mutter a gaali under my breath. Everyone in school knows: here, relations always win over rules.

He flicks his wrist, gold ring flashing, like even the helpers are beneath him. Once, I watched him wipe sweat from his forehead with a handkerchief—then fling it at a junior boy to pick up. That’s his style: lord of the canteen, king of nothing.

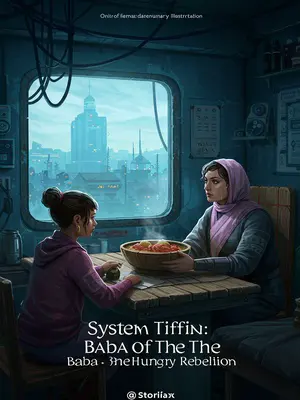

The chicken leg and my great-grandmother were born the same year, I swear on my tiffin. Not even joking, yaar. The first time I saw that shriveled chicken leg, skin hanging like my dadi’s arm, I wondered if someone dug it up from an archaeological site. The smell hit me first—like the mothballs in my nani’s old trunk. Even the flies seemed to think twice before landing. When I poked it with my spoon, the meat nearly turned to powder.

Meatballs made entirely of fat—eight rupees a piece. Imagine, for eight rupees, you get this squishy, greasy thing that slips out of your mouth if you’re not careful. Break it open, and oil floods the plate, just like Mumbai roads after the first rain. Sometimes I wonder if canteen uncle just collects leftover paratha oil for these meatballs.

No matter how much masala they dump in, nothing hides the rotten stink of the duck meat. Red chilli, cumin, dhania, a full lemon—doesn’t matter. The smell floats up your nose, just like that time a rat died behind our fridge and the stench wouldn’t leave for days.

Just like no amount of excuse—however righteous—can hide the principal’s greed. Principal sahab stands on stage at assembly, preaching ‘values’ and ‘integrity,’ but everyone knows he’s getting his cut from the canteen. You can see it in the way his eyes dart whenever someone brings up food complaints. Log kya kahenge, he says, but really, he just cares about what’s lining his pocket.

I really couldn’t take it anymore. So, I led my classmates, and we overturned the canteen’s food trays.

Right before we did it, we exchanged glances. Someone nervously cracked their knuckles, the clatter of steel plates echoing in the tense silence. Then—crash! Curry splashed, trays clanged. For once, the whole mess hall stood together—not a whisper of protest. Our hands sticky with gravy, shoes slipping on spilled sambar, hearts pounding with something close to pride. For a minute, we felt like freedom fighters, taking our dignity back from a mini-dictator.

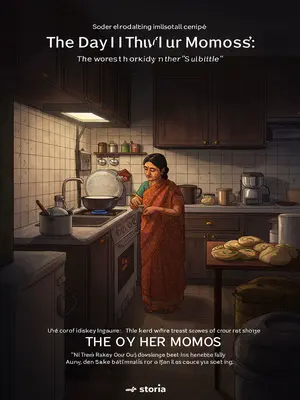

The principal called my parents in and demanded I apologise. He sat across from me in his freezing AC office, pen tapping on the complaint register. “This is too much, beta! What kind of behaviour is this? You think you can just break rules and get away?” he thundered, acting like I’d set the whole school on fire.

My parents were furious: “We pay so much for your meals every month, and this is what you feed our child?” Mummy’s voice rose, making the glass panes shake. She adjusted her pallu and tapped her forehead in frustration. “Aap log ko sharam nahi aati?” she snapped. Papa’s hands tightened around the steel tray he was holding, knuckles white with controlled rage. Even the peon bringing water looked away, embarrassed for the principal.

Then Papa slammed the meal tray right in front of the principal. “You eat this, right here, right now. If you dare to leave even a single grain of rice, we’ll see each other at the Education Department.”

The sound of the tray hitting the desk rang through the room. The principal’s glasses slid down his nose. For once, he had no comeback. I felt a strange thrill—like the weight of every insult I’d swallowed in the canteen suddenly lifted off my chest. Mummy glared, daring him to protest. Papa’s threat about the Education Department was peak Indian parent—using sarkari power as the final weapon.