Chapter 2: Birth and Bitter Lessons

I transmigrated.

It was as if I tumbled through the space between two dreams, waking up to the wail of a newborn—my own. I became a newborn baby girl, small like a fresh akara ball.

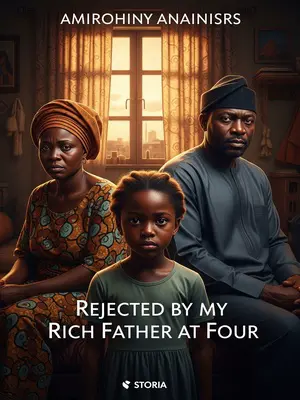

Everything around me was warm and raw—the sharp smell of palm oil, the voices of aunties chattering, the cool press of cotton cloth against my skin. I could feel the weight of many eyes watching as the midwife wrapped me in ankara and carried me to my father, his face long like Monday morning.

Because I was a daughter—again.

You could almost taste the disappointment in the air. Another girl. Some aunties made small sounds in their throats, side-eyeing my mother on her mat. Still wrapped in cloth, I used all my strength to squeeze out a smile for him.

Everybody in the compound started to marvel, clicking their tongues, saying this must be a God-sent father-daughter bond.

One old uncle even tapped his staff and said, “Omo yi, e go bring better for this house! Mark my words—she go change this family story.” Only then did my father finally carry me from the midwife’s arms, a small smile finally breaking through.

From that moment, I understood: coming as a daughter in olden days is not like all those sweet romance stories.

The world in the books never mentioned the bitterness that lingers after a woman gives birth to yet another girl. They never talked about the weight of expectations that pressed down on such tiny shoulders.