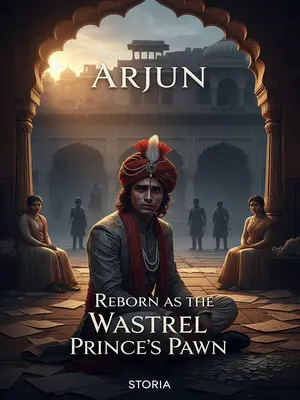

Chapter 1: The Raja Is Dead—Long Live the Raja

I, the Raja, am dead:

After slogging away for thirty years, I finally died of exhaustion.

The thing is, in our desh, dying of tiredness isn’t all that rare—especially if you’re the Raja and nobody lets you have your chai in peace. Even in my last days, it was always files, complaints, petitions, and endless ‘urgent’ meetings. Who knew, after all that, I would simply collapse one evening, my forehead sticky with sweat and the distant sound of the pressure cooker whistling from the palace kitchen. Somewhere, the faint aroma of frying onions drifted in, almost drowning out the smell of old paper and ink. My end came as quietly as a fan turning off during a power cut—sudden, awkward, but not entirely unexpected.

But apparently, I haven’t completely kicked the bucket…

That very night, I woke up in the Crown Prince’s body.

And just like that, without warning, the world tilted on its axis. The sweet smell of mogra from the pillows was still the same, but my hands—ah, so much younger, no sign of the old burn scars from that Diwali accident. I sat up, feeling my heart hammer, the memories of my own funeral blending with the lingering taste of kaju katli from the offering tray. My breath caught in my throat. I clutched the sheet, half-expecting Amma’s scolding voice to call me for tea.

The moment I realised I’d swapped shells, I just stood there, dazed:

It’s a strange thing, looking into a polished silver thali and seeing your own son’s face staring back, blinking with disbelief. The velvet drapes hung heavy in the morning air, and even the pigeons seemed to coo a little softer that day, as if sensing something had shifted in the mahal.

As for suddenly becoming my own son—well, I’m still not over it.

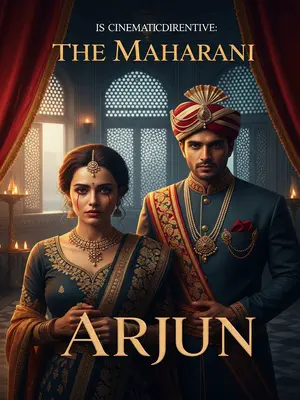

It wasn’t until the Maharani pinched my thigh—hard—that I snapped out of it. Arrey, I have to cry at my own funeral!

She leaned close, her eyes glinting, and whispered, “Don’t mess this up.” Only then did her fingers dig in. I could only stare at her, eyes wide, wondering whether she’d lost her mind or if I had. The pinch was so sharp, I nearly yelped, but then remembered, this is not the time for confusion. Maharani’s bangles clinked as she readied herself to guide the scene; my mother—now technically my wife—never lets anyone mess up the script.

For the first time, I discovered that my always delicate and gentle Maharani actually has quite a grip:

The way her fingers dug in, it reminded me of how she used to wring out wet sarees on the balcony, arms steady, face all seriousness. Who would have thought, behind that innocent smile and the habit of feeding stray cats, she harboured such strength?

With a twist and a squeeze, smooth as ghee, crisp and ruthless—

In that moment, she was like those ladies at the vegetable market, bargaining with the sabziwala for every last paisa—unyielding, quick, and precise. Not a bead of sweat on her brow; only determination. I felt the pain shoot up my leg, my toes curling in shock.

My tears gushed out instantly.

Seeing this, she finally relaxed and let out a sigh. “Cheenu, don’t just stand there, hurry up and step forward…”

She said this while shoving me forward with all her might.

I wasn’t paying attention and—dhadaam!—I face-planted right on the marble floor.

The marble floor was icy against my cheek, and I prayed the family WhatsApp group wouldn’t get wind of this. For a moment, even the conch shells outside paused, as if the whole mahal was holding its breath. Somewhere in the verandah, a maid dropped a steel lota. The awkwardness spread like spilled chai on a white kurta.

The Maharani was stunned.

The ministers nearby were stunned.

I couldn’t help but sigh inwardly—after sharing a bed for over twenty years, I never noticed anything unusual. The Maharani, truly, is a master at hiding her talents.

As the scene grew more and more awkward, I quietly sighed and started to wail, “Pitaji Maharaj, your son is unworthy…”

I did a proper pranam, turning my flop into a kneel, and shuffled forward on my knees to the sandalwood coffin.

The air was thick with agarbatti smoke, the faint rustle of silk sarees, and muffled sobs. The sandalwood aroma mixed with rose petals scattered on the floor, sticking slightly to my palms as I touched my forehead to the marble, as Dadi taught me. It was the first time I noticed how cold the marble felt in June, even with the old air cooler groaning in the corner.

The atmosphere finally smoothed out again.

Sure enough, without me, this family would fall apart.

I could even hear everyone around me breathe a sigh of relief, then start crying and comforting each other. Of course, the loudest were those praising the Yuvraj’s great filial piety, their voices intentionally or not drifting into my ears from all directions.

One minister whispered just loud enough, “A son like this, truly a gem for Bharatpur.” Somewhere, a sniffling cousin muttered about the lines of succession—‘Arrey, ab toh sab theek ho jayega na?’—relief fighting with greed in their voices.

Crying at the Raja’s funeral is a technical skill.

You can’t look too sad, but you can’t look not sad enough either.

If you don’t cry properly, the court chroniclers will scold you for being eager to inherit the throne—unfaithful and unfilial. But if you cry too much, they’ll say you’re weak and sentimental, unfit for responsibility.

I have deep experience with this.

When my great-grandfather died, my grandfather was so grief-stricken he couldn’t stop crying, and the nosy chroniclers criticised him for years. Even when he issued orders later, there were always those who thought he was soft-hearted and tried to take advantage.

Later, when my grandfather passed, the late Raja learnt from that lesson—he restrained his emotions, acted generous and proper, clear and orderly. Then they said he was cold and lacked filial piety.

Having grown up watching this, I figured out my own countermeasures early on.

When the late Raja died, I cried bitterly, recalling every bit of our relationship, silently reciting his teachings, and fully displaying the heart of a devoted son and the intent of a king.

It was all about moderation.

Like making the perfect dal—too much salt, too little tadka, and everyone will complain. There is a proper andaaz, an exact measure, even in tears.

The old ministers beside me kept bowing to show their loyalty.

This is probably the first test for a new Raja.

But honestly, I really can’t cry right now.

Even after more than thirty years on the throne, mastering all sorts of emotions, facing my own photo garlanded on the wall is just… awkward, no matter how you look at it.

From across the hall, I caught a glimpse of my own photo, framed with bright marigolds and jasmine, a small diya flickering underneath. For a second, I had to suppress a laugh—my moustache in the photo was looking especially crooked, courtesy of the palace photographer who insisted on ‘natural’ poses.

After the pain in my thigh faded, the tears dried up—but that was only the start, and it clearly wasn’t enough.

So I had to raise my sleeve to cover my face and start fake-wailing.

I let out a series of shaky, hiccuping sobs, pretending to wipe away tears as my mind wandered to the taste of my morning chai. Even the family dog, Motu, looked up from beneath the divan, tail thumping in confusion at the noise.

The Maharani was the first to notice something was off. She tugged my sleeve, then—faster than lightning—wiped my face with her hand.

Spicy.

Burning.

My eyes, my nose, my skull—

Arrey, that’s intense!

My tears and snot streamed down together.

The Maharani nodded in satisfaction, looking like she’d do it again if it wasn’t enough.

I gazed at her through my tears:

Maharani, I never knew you were so clever and resourceful.

Underneath those lotus eyes and gentle smile was a woman who could outfox a whole room of politicians. That day, as she patted my back, I felt oddly proud. For all my life, I’d overlooked so much about her. Maybe it was finally time to pay attention.

But if I thought dying would finally let me rest, I was about to be proven very, very wrong.