Chapter 6: The Last Supper

I put on my helmet, started the bike, and took less crowded side roads. On the way, I passed a still-open pharmacy and bought dozens of boxes of common medicines, plus some Dettol and gauze.

I stuffed the medicines in my backpack, the pharmacist barely glancing at me. He was already packing up, his shelves half empty, eyes haunted with worry.

Two hours later, I finally arrived at the foot of Shivgiri Hill. From a distance, I saw my papa’s truck had just pulled up.

The old green Mahindra looked like it had seen a hundred harvests, dust caked on the tyres, a jute rope holding the rear door shut. Papa’s hat was perched at a jaunty angle, as if defying the end of the world.

I slowed down and shouted, “Papa, drive up—follow me!” Back in college, I’d brought friends here a few times, so I knew there was a cement road behind the hill that led straight to the viewpoint halfway up.

The air was cooler near the trees, the sudden silence broken only by the cawing of crows and the distant echo of temple bells. The forest seemed to hold its breath.

The bike’s roar echoed through the forest. Along the way, we didn’t see a single person—only flocks of birds circling the hilltop. It seemed the animals already sensed the coming disaster.

Even the langurs that usually hung around for food scraps were gone, the only movement a stray squirrel darting up a tamarind tree.

At the viewpoint, my parents and I hurriedly unloaded the truck. Besides thirty bags of potatoes, the rest was all wheat.

My maa, sari tucked in at the waist, was directing operations with the efficiency of a military commander. Papa carried bags on his back, refusing to let me help with the heavier ones.

Time was tight—I didn’t dare stop for a second. After a brief rest, I left the axe with my maa for self-defence, had her stay to watch the supplies, and went with my papa to drive the truck home for another load.

Maa gave me a stern look, her eyes saying, 'Come back safe.' She gripped the axe like a seasoned warrior, her bangles clinking as she adjusted her dupatta and kept watch.

Maa had already packed up all the important household items: two iron kadhais, steel bowls and basins, iron buckets—all sturdy and durable, stacked neatly in the corner. Several jute bags were stuffed full of quilts and clothes.

She’d even remembered the old pressure cooker with the bent handle and papa’s lucky steel tiffin. Those little things, the backbone of any Indian kitchen.

Other things were already packed, but there was no time to check what they were—we just took whatever we could.

A battered photograph of my grandparents peeked from a corner, and a faded Ganesh idol made its way into the pile. Superstition or not, I couldn’t leave it behind.

After loading up the second batch, I locked the door, took one last look at the small courtyard house I’d lived in for over twenty years, and jumped onto the truck.

That old neem tree, the hand pump, the paint peeling from the walls—I memorized it all in a heartbeat, not knowing if I’d ever see it again.

Papa started the engine and headed straight for the town’s seed shop, buying a large batch of fruit, vegetable, and grain seeds.

The shopkeeper, bewildered but obliging, packed up everything in brown paper bags. 'Better safe than sorry, bhaiyya,' he muttered, wiping his glasses.

By the time we returned to the viewpoint halfway up the hill, it was already 7 p.m. From morning until now, I hadn’t eaten a bite or drunk a drop of water—just running on sheer willpower.

The sun was a blood-red disc sinking behind the hills, the air buzzing with insects. My throat was parched, my head light from hunger, but there was no time to complain.

Now, finally safe for a moment, I relaxed and suddenly felt completely exhausted and starving.

Every bone in my body ached, and I flopped onto a sack of potatoes with a sigh. Maa’s face softened as she saw me, her hands gentle for the first time that day.

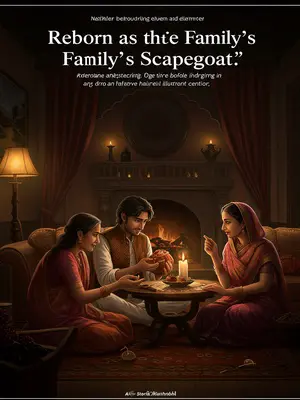

Fortunately, Maa had packed up all the remaining dry food and vegetables at home. She climbed onto the truck, rummaged around, and pulled out a big red plastic bag. From inside, she took out a few rotis and a bottle of achaar, then a small green chilli. She expertly dipped the chilli in achaar, spread it on a roti, rolled it up, and handed it to me.

Maa’s hands, rough from years of kneading dough, were gentle as she tucked a strand of hair behind my ear.

The roti was still soft, the achaar sharp and salty, the chilli burning a line down my throat. It tasted like home, like everything I’d fought for.

I devoured it hungrily.

In two bites, it was gone. Maa laughed and shook her head, as if I were a child again.

“Eat slowly, don’t choke,” Maa said, smiling, handing me a steel bottle. “Have some water.”

The water was cool, the steel bottle heavy in my hand—a reminder of countless school tiffins and picnics.

Looking at my family sitting together in a circle, I felt like this was the best meal I’d ever had.

There was peace in that moment, the world reduced to the circle of lamplight, the soft sound of wheat sacks settling, the night song of crickets.

After eating and drinking, I told my parents in detail about the disaster from my previous life. I didn’t know if the sea would flood Shivgiri Hill—only that, when I was struggling in the water at the end, I could still see the vague outline of Shivgiri Hill in the distance.

They listened in stunned silence, Papa’s hand never leaving Maa’s shoulder, Maa’s eyes searching my face for any hint of a joke. But I was dead serious. The old ways of life—faith, doubt, hope—all mingled in their silence.

Based on that, my parents and I quickly made a plan: head to the summit, the highest point on the hill. There was a white temple at the top, built of reinforced concrete. It didn’t cover much ground, but it had five floors and only one entrance—easy to defend, hard to attack, even if others came.

I remembered the temple’s cool stone floors, the echoing chant of 'Om Namah Shivaya' in the early mornings, and the musty scent of incense—now, it was going to be our citadel.

But with less than sixteen hours before the disaster started, and no road further up, the truck couldn’t reach the summit, so it was impossible to move all the supplies from the viewpoint.

Papa frowned, thinking hard. Maa tied her dupatta tighter, determination shining in her eyes. We didn’t have the luxury of arguing or panicking—only action would do.

Next, we had to sort the supplies again and take only the absolute necessities first.

The night air was heavy with the scent of mango blossoms. Somewhere, a dog barked in the village below. My heart pounded, but I felt a new resolve settling in.