Chapter 7: Temple on the Hill

A set of spatulas, three steel bowls, several pairs of spoons, and two kitchen knives—all went into the iron bucket. That was all our cooking equipment.

The bucket was battered but sturdy, the kind that had survived a thousand dal washes. I tied it with a length of rope, making sure it wouldn’t spill.

Clothes and quilts took up too much space and were hard to carry. Besides, the temperature was over 27°C now, so we didn’t need to worry about warmth yet. I only took a few sheets, which could be used as bundles or ropes in a pinch. The rest of the jute bags full of clothes and quilts I tied to tree trunks, so they wouldn’t be washed away by water. If we survived, we could come back for them later.

I made sure to knot the ropes tightly, Dadi’s old saree pressed into service as extra padding. Everything else was left behind with a whispered prayer.

Other essentials included the rest of the dry food and vegetables, crop seeds, salt, fever and anti-inflammatory medicine, Dettol, matchboxes, candles, and of course my axe—essential for survival in the hills.

A matchbox tucked into my shirt pocket, the bottle of Dettol snug next to it. The seeds were bundled in a cotton dupatta—life in a packet, if we were lucky.

Even after trimming down to just survival necessities, there were still two big bags. I tied them to the bike and took them to the summit first. My parents stayed behind to tie up everything else and secure it to trees.

I kicked the bike into gear, the climb steeper now, tyres skidding on loose pebbles. Sweat poured down my face, but I didn’t stop.

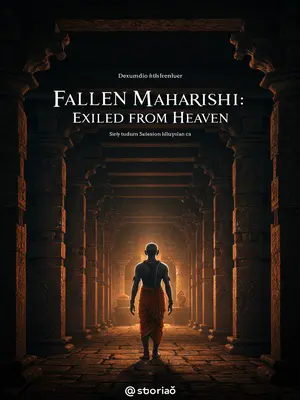

The rugged hill path, long unused, was overgrown with weeds. After a rough ride, I finally saw the white temple at the summit.

The temple was silent, its paint peeling, the trident on the dome gleaming faintly in the moonlight. A stray dog barked in the distance, then fell silent.

The entrance was a heavy iron door, with a rusty padlock hanging on it. I took out my axe and chopped down—the lock fell to the ground.

The sound echoed around the empty hilltop, startling a couple of pigeons out of their roost. I muttered an apology to Lord Shiva, hoping He’d understand.

Opening the door, I found the inside thick with dust. Clearly, no one had been here in a long time.

Cobwebs hung from the corners, the air was stale, the smell of old incense lingering faintly. I coughed, waving dust motes from my face.

I quickly swept the floor, set down the supplies, and went back for my parents.

The cool stone floor felt good under my aching feet. I lined up the bags, making sure nothing was in the way of the door. Then I ran back down, my lungs burning with each step.

After bringing my parents up one by one, it was already midnight. Though exhausted, I was running on adrenaline and made several more trips to the viewpoint, bringing up thirteen chickens and several bags of potatoes and wheat.

The chickens clucked indignantly, feathers ruffled. Maa soothed them with murmured words, her hands gentle. Papa and I staggered under the weight of the bags, but we didn’t dare rest.

At five in the morning, I finally couldn’t hold on anymore, spread a sheet on the floor, and fell asleep.

The stone was cold, the world finally silent. I closed my eyes, a prayer on my lips.