Chapter 3: Life in Exile

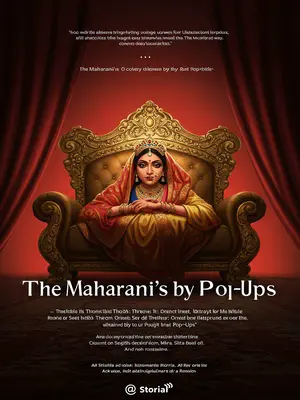

I remained a princess, but not the Maharaj’s true daughter.

The old ladies in the palace would still call me "Rajkumari," but the warmth was gone from their voices. Their glances slid away, quick and nervous.

I was the daughter of the king’s favourite consort, and because of her favour, I was granted the title of princess.

In the women’s quarters, I heard them mutter over their embroidery hoops, their voices sharp as the needles in their hands: "She’s here only because of her mother’s beauty, not her own blood."

Others rise through palace intrigue.

They say, "In this palace, you climb by guile, not birth." My mother’s ascent was whispered about at every mehfil.

My mother rose by stealing a kingdom.

She walked those halls with her chin high, but I saw how everyone’s eyes followed her, calculating.

But I always felt it wasn’t worth it. After all her effort, she only gained a single rank.

My mother’s anklets may have tinkled in the Maharaj’s chambers, but her voice was just one among many.

Now, my mother is indeed favoured, but anyone with eyes can see the Maharaj does not love her.

Her smile is painted on; his laughter never reaches his eyes when he looks at her. The courtiers see it too—they never bring her real power, only silks and gifts.

The Maharaj of the North loves no one; he loves only power.

He is a true son of the North—cold, calculating, never showing real affection. Even the birds in the palace gardens seem to grow silent around him.

My mother, this beautiful tool, continued to shine in the harem after being used.

Her eyes still sparkled, yet sometimes I caught her staring into nothing, as if searching for something lost.

But my mother didn’t see it that way. I always felt she was trapped in a splendid dream.

Her voice would grow dreamy, as if she was a heroine in a folk tale, destined for great love.

I once thought she betrayed Father out of loyalty to her homeland.

Sometimes, in rare moments, I would wonder if she missed her old home, the northern hills, the chill in the air, the scent of pine.

But that wasn’t it. She was simply addicted to love.

She lived for attention, for the thrill of being the centre of every room. No nation, no family, only the next heartbeat, the next adoring glance.

Yet, the one she loved was not my father.

She would sit at her mirror, humming old northern songs, lost in memories of another man.

It was the current Maharaj of the North.

I heard the old maids whisper—how she met him as a young girl, how his shadow never left her heart.

I became mute. The palace doctor said I was traumatised.

He brought me sweet betel leaves and tried to coax words from my lips, but I stared through him, silent.

I don’t know if I was truly traumatised, but I certainly didn’t want to speak.

My voice seemed trapped in my chest, locked away with my childhood.

I still lived in the palace where I grew up. They said the north was too cold, so after Kaveripur fell, the capital was naturally moved here.

The palace gardens had new flowers, the walls hung with northern tapestries, but everything smelled different—like sandalwood mixed with unfamiliar herbs.

Mother was still mother, the palace still that palace, but I disliked everyone here.

The language was harsher, the customs strange. I clung to the shadows, avoiding the endless festivities.

Mother wanted me to call the Maharaj ‘Papa’, but I refused, because I could no longer speak.

I would turn my face away, biting my lip when she urged me. Her eyes grew stormy with each refusal.

She was disappointed, and a faint dislike for me began to show.

Her scoldings grew sharper, her touch less gentle. "Such a stubborn girl," she would sigh in the ladies’ hall.

But the Maharaj didn’t care much. He treated me well and often sent me gifts.

Fine silks, sweetmeats from the royal kitchen, a set of golden anklets that chimed softly when I walked. But his eyes never softened for me.