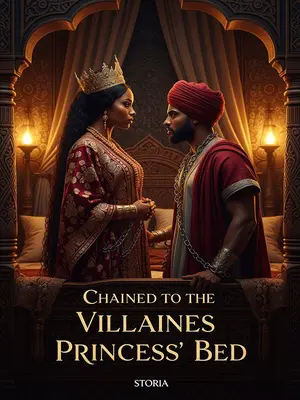

Chapter 2: When Trouble Comes

---

Big wahala burst: my brother talk anyhow for council meeting, vex the king, and dem carry am go put for the royal cell—the 'King’s Cell' wey dem dey use for serious crimes.

That day, my brother Tunde’s voice echoed round the palace courtyard, and the elders grumbled under their breath. The king’s chiefs shook heads, their heavy beads clicking. The dust from the courtyard rose as Tunde struggled, mixing with the smell of burnt palm oil from the palace kitchen. When Tunde was dragged out, his wrapper half-loose, I could only bite my tongue, tears burning my eyes. Palace whispers spread faster than harmattan fire—everybody knew trouble had landed.

When the news reach house, my papa and mama just faint.

My mother’s wrapper slipped from her shoulder as she collapsed, hands trembling, while papa’s cap rolled under the settee. 'Jesu! Oluwa, help us!' she cried, clutching her chest as she fell. Our neighbours crowded the verandah, whispering prayers and fear.

Before my mama even pass out finish, she grab my hand strong, tears just dey flow as she beg me, "Morayo, na only this one elder brother you get o. You must find way save am."

Her grip hurt, her fingers digging into my palm. She pressed her forehead to mine, hot tears soaking my cheek. "Na you get sense pass for this house, Morayo," she whispered, "make you use am well. Don’t let Tunde rot for cell."

I sit down for parlour alone all night. At last, I bite my teeth, find person to help me, and send myself go land for the king’s bed.

The ticking of the old wall clock echoed as I sat, my arms hugging my knees. The scent of fried onions from the neighbours’ house floated in. The midnight cockerel crowed early, as if warning me. In the end, I folded my wrapper, tied my scarf tight, and knocked on the window of my mother’s cousin, Ireti—she helped me pass word into the palace.

Night don deep, compound lanterns dey shine. I sit for corner of the king’s room, my mind just dey waka.

A lazy moth circled the lantern, wings beating against glass. My breath steamed in the harmattan air, thick with tension. My eyes darted to the palace clock, counting down the minutes to Obiora’s return.

One palace maid wey sabi me say Obiora don dey busy with council work these days, dey wake early, sleep late. To save time, he dey always stay for side chamber, e never even enter women’s quarters for long.

The gossip in the palace kitchen was plenty—Obiora kept away from most women, buried his head in council matters. He’d rather sit with old chiefs, even if their stories bored him half to death.

To be honest, even before, he no dey enter women’s quarters like that.

When he was just a prince, the other women used to tease about his shyness. The king’s youngest wife once joked, "That one, if you show leg, he go run pass antelope!"

Three years since he become king: only few wives, no pikin for him side.

Aunty Ireti used to sigh and say, "Maybe his star no shine for children yet." The town gossips spun wild tales, but the palace midwives kept quiet, out of respect—or fear.

People for outside dey talk say the king get sickness, say he no sabi anything for bed.

Palace guards would snicker behind their hands, market women gossip by the pepper stand. "That king, na only mouth him get!" they would cackle.

Na big lie be that.

I knew the truth. The scars on my hips from that long-ago night with Obiora—those were not sickness marks. Not everything the market gossips say be true. Some things only belong to the two people who shared them.

Nobody know pass me say Obiora sabi make person suffer for that side.

The memory flashed hot through me—Obiora’s hands, rough and soft, his body pressed to mine. My skin tingled even now. Shame and longing twisted together, mixing in my belly, as I waited in the shadowy room for the king who had once been mine.