Chapter 5: False Accusations

Early the next morning, Shyamlal’s shop did not open.

Usually, the smell of burning agarbatti and the clang of the shutter signalled the start of a new day. That morning, only silence greeted the lane.

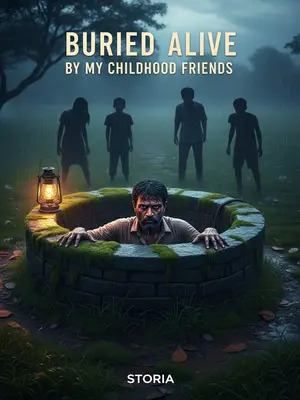

A neighbour, sensing something was wrong, entered and found he had hanged himself inside.

The news spread like wildfire—before the sun was fully up, half the village had gathered outside the shop. Some women wept, some men just shook their heads, muttering, "Bhaiyya, ek aur zindagi barbaad ho gayi."

When we arrived, we saw that garbage had been dumped at his door. Red paint had been splashed on the front, with crude, filthy words scrawled across it. Even the wall beside the shop had obscene graffiti.

Broken glass, half-eaten rotis, and empty plastic bottles littered the front step. The curses painted on the wall made even the constables wince.

We learned all this had been done by villagers after we took him away, to curse him.

One old woman, hiding behind her veil, confessed quietly, "Log bahut gusse mein the, beta. Kya karein, gussa nikalna tha."

But our test results were in: Shyamlal was not the one who assaulted Anjali.

Kunal ran a hand through his hair, muttering a curse in Hindi under his breath as he slammed the report on the desk, voice choked with frustration. "Nirdosh tha, fir bhi mar gaya."

So, most likely, he was not the one who assaulted Priya, either.

We sat in silence, the full horror of what had happened settling over us like a suffocating blanket. A life destroyed, justice still out of reach.

Even so, as we handled his remains, villagers still whispered that he had killed himself out of guilt.

The grapevine was relentless. "Agar kuch nahi kiya hota toh marna kyon tha?" someone muttered. No amount of evidence could silence suspicion.

We all knew he wasn’t a suicide. What truly killed him was malicious rumour.

In our hearts, we mourned—not just for Shyamlal, but for the cruelty that small communities can unleash in their thirst for easy answers.

But another question arose: if Shyamlal wasn’t the perpetrator, why did Priya accuse him?

Kunal looked at me, eyes narrowed. "Yeh to samajh mein nahi aata, bhai. Kisne dabaya hai usko?"

At the same time, we received bad news about their other classmate, Meena.

The constable’s voice was grave over the phone, "Meena ke saath bhi wahi hua, sahib."

Meena was also a left-behind child, living with her grandmother while her parents worked out of state. She hadn’t had a chance to be examined the day before, when Priya’s case exploded.

Her grandmother, a frail woman who sold vegetables by the highway, pulled her close, as if her embrace could shield the child from everything that had happened.

But after that incident, her grandmother quickly arranged for her to be checked at the hospital. The result was the same: hymen rupture.

The nurse shook her head sadly, ticking another box on the medical form. The weight of sorrow seemed to add years to her face.

While we were still negotiating with the panchayat about Shyamlal’s aftermath, Priya’s parents and Meena’s grandmother had already gone to the committee to demand justice.

They stormed into the panchayat hall, voices raised, demanding answers. A crowd gathered outside, eager for drama.

They didn’t bring the children, only their outrage.

The children were kept at home, hidden from prying eyes. The adults, on the other hand, were loud and determined.

At first, we thought they were angry at us for being slow to find the real culprit.

Kunal muttered, "Inko lagta hai hum kuch nahi kar rahe hain."

But that wasn’t it.

Their anger was not about justice. It was something else—a simmering desire for compensation, for something tangible to fill the void.

They didn’t seem to care about the real culprit at all.

It became clear when Priya’s father said, "Shop toh band ho gaya, ab humare bachchon ka kya hoga?"

Because after venting their anger, what we heard was:

“Now that Shyamlal is dead, how will he compensate our children for their suffering?”

Their voices rose in unison, "Ab kaun dega paisa? Kaun bharega inka nuksaan?"

That’s right—even though we’d emphasised that Shyamlal was not the real culprit, they didn’t care.

They shrugged, unconcerned. One man said, "Sahab, galti kiski bhi ho, kuch toh milna chahiye."

Things became even more chaotic as they began making demands: asking us to unseal Shyamlal’s shop, search for his assets, and give them to their children as compensation.

The panchayat elders looked helpless, promising everything and nothing at once. Someone even suggested auctioning Shyamlal’s bicycle.

Of course, we couldn’t agree. Shyamlal’s affairs hadn’t been settled, and the shop was still sealed.

We explained, "Ye sab kanooni karwai ke baad hi hoga. Abhi kuch nahi ho sakta."

The panchayat was also helpless, only promising to resolve things quickly, find the real culprit, and—of course—provide compensation as soon as possible…

The sarpanch, an old man with trembling hands, kept repeating, "Sab ho jayega, beta. Thoda sabr rakho."

After a lengthy argument, they finally left, though reluctantly.

As they walked away, the murmurs of dissatisfaction drifted back to us. The sense of injustice lingered, thick as the dust swirling in the air.

This left me with a strange feeling.

I wondered, not for the first time, whether truth really mattered to anyone anymore, or if suffering had become just another bargaining chip.

At least for Priya’s parents and Meena’s grandmother, it seemed the truth about the children’s abuse didn’t really matter. What they wanted was compensation.

Kunal shook his head, "Ajeeb baat hai, yaar. Paisa sab kuch ban gaya hai."

Another point: during the dispute, we suggested that the investigating officers communicate with the girls again. But the guardians all refused.

"Bachchon ko aur mat satayiye," Priya’s mother pleaded. "Jo poochna tha, pooch liya."

Looking back, from the moment the case broke until now, no one had been able to speak with the girls alone. Every conversation required the guardians’ authorisation, and they were always present.

Even at the thana, the women would crowd the room, refusing to step outside. Every word was filtered through adult anxieties and agendas.

At first, I thought they were just protecting the children. But after the panchayat incident, I had another thought: maybe they didn’t want us to learn anything from the children. Maybe accusing Shyamlal wasn’t truly the girls’ own intention.

The possibility gnawed at me. Kunal, too, began to wonder if the adults were orchestrating the narrative for their own ends.

But at the time, we really had no way to bypass the guardians and question the girls directly.

The social structure in the village was ironclad. A police officer could not, under any pretext, question a minor girl alone—not without the risk of another scandal.

So, the case stalled again.

Files piled up, and the monsoon clouds darkened the sky. Days passed with no progress, only frustration.

We could only try a different approach.

Kunal suggested, "Kahin na kahin se kuch toh milega. Park ka angle dekhte hain."